By Doug Boilesen

The

first movies seen by the public using

Edison's Kinetoscope in

1894 were without sound. Edison's intent from the beginning, however,

was that recorded sound should be part of a multimedia "moving

pictures" experience.

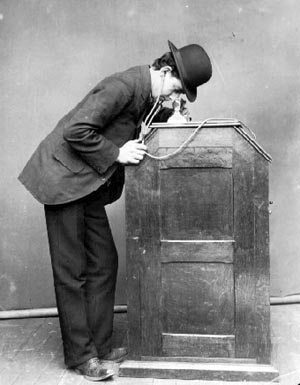

Edison

had hoped to introduce his moving picture "Kinetoscope"

at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition and had promoted it as something

which would include sound. His Kinetoscope 'peep-show' entertainer

was not ready before the Exposition ended, and when the first Kinetoscope

Parlor was opened on April 14, 1894 in New York City the phonograph

was still not part of Edison's moving picture device.

The

First Soundtracks

In

1895 Edison introduced his Kinetophone (a combination Kinetoscope

and Phonograph, also known as the Phonokinetoscope) with its peep-show

viewer for watching the moving pictures and ear tubes for listening

to the phonograph. "Most, and probably all, of the films marketed

for the Kinetophone were shot as silents, predominantly march or dance

subjects." These movies created for Edison's kinetophones, however,

did allow exhibitors of Kinetophones to "choose from a variety

of musical cylinders offering a rhythmic match." (Altman, Rick,

Silent Film Sound, (2007), pp. 81–83; Hendricks,

Gordon, The Kinetoscope: America's First Commercially Successful

Motion Picture Exhibitor. (1966), pp. 124–25).

The cylinder records selected

and played by the kinetophone exhibitors, therefore, could be called

the first soundtracks of the movies. For example, suggestions

of "three different cylinders with orchestral performances

were proposed as accompaniments for Carmencita: "Valse Santiago",

"La Paloma", and "Alma-Danza Spagnola." -

(Wikipedia, Guida practica (1895–96), p. 126 [p. 348 in Light

and Movement]). Since Emile Berliner patented the 'Gramophone'

in 1889 it wouldn't have been an anachronism to have Grammy Awards

in 1895 so perhaps one of those recordings could have won the "1895

Grammy Award for Best Score Soundtrack for Visual Media."

Screenshot from Carmencita,

the 1894 Edison short named for the featured dancer of the film, could

have been seen and heard on a Kinetophone in 1895.

WATCH

Carmencita (Source: Library of Congress).

LISTEN

to La Paloma by the Edison Symphony Orchestra, Edison 2-minute

Cylinder Record Number 565, Released 1902 (David Giovannoni Collection).

The Kinetophone was unsuccessful

with only "forty-five of the machines were built over the next

half-decade." (Musser,

Charles, The Emergence of Cinema: The American Screen to 1907,

(1994), p. 88.)

The

First Projected Movies

The first public screening

which projected moving pictures was by the Lumière brothers (Louis

and Auguste) using their Cinématograph on December 28, 1895 at the

Grand Café in Paris. Projected moving pictures would soon dominate

the way moving pictures were watched and significantly impact the

kinetoscope market.

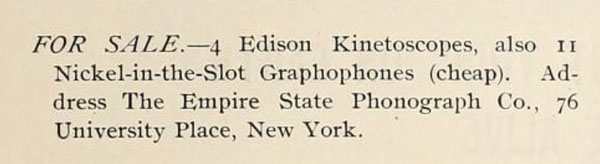

"Wants and For

Sale," The Phonoscope, April 1897

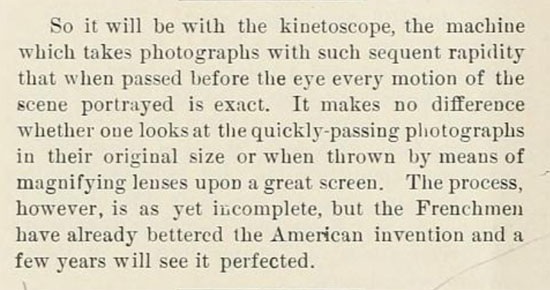

The trade magazine The

Phonoscope reported in their November 1897 issue that the Frenchmen

had already bettered the peep-show kinetoscope and in a few years

their projection system will be perfected:

The Phonoscope,

November 1897

Projected

Feature-length Movies

In 1906, the first feature-length

silent film titled "The Story of the Kelly Gang" was produced

in Melbourne, Australia. The film was directed by Charles Tait and

was about the outlaw Ned Kelly and his gang. "In

2007, "The Story of the Kelly Gang" was inscribed on the

UNESCO "Memory of the World Register" for being the world's

first full-length narrative feature film." Wikipedia.

William S. Porter's 12-minute

"The Great Train Robbery" released in December 1903 and

distributed by the Edison Manufacturing Company has often been called

"the first Western or even the first film to tell a story."

Film scholars, however, "have repeatedly disproved these

claims." Nevertheless, "its commercial success and

mythic place in American film lore nonetheless remain undisputed....In

1990, "The Great Train Robbery" was selected for preservation

in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress

as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Wikipedia (extracted 7-10-2024).

Projected silent movies

would continue to thrive and recorded sound would take some time to

become an expected part of the movie-goers experience.

Projected

Movies and synchronized recorded sound

Leon Gaumont's projector,

the Chronophone, was introduced in 1902 which successfully produced

"several hundred Phono-Scenes by 1912 which used his projector

and a synchronized gramophone sound system.

Leon Gaumont's Chronophone, a

system that used a rheostat to synchronise the speed of a projector

with that of a gramophone, was introduced in 1902, and by 1912 he

had produced several hundred Phono-Scenes, mostly popular songs

or extracts from operas and ballets. Sound effects were common in

fairground performances, and in cinemas, actors would sometimes

be concealed behind the screen, speaking in synchrony with the characters

in the film. More important, in Burch's opinion, was the lecturer,

who would explain and comment on the action, constructing a continuity

out of a fragmentary narrative and indicating how the audience should

respond. "Silent Film" edited by Richard Abel, The

Sound of Silents, Rutgers University Press, 1996, (Chapter by

Norman King "The Sound of Silents", p. 32).

Edison introduced his

new Kinetophone in 1913 using a projecting kinetograph and phonograph

system with a cylinder record but for a variety

of reasons by 1915 he had abandoned it. Watch one of the surviving

Edison Kinetophone

demonstrations of moving pictures, dialogue and music (The Musical

Blacksmiths) from 1913.

The

Musical Blacksmiths, Kinetophone 1913

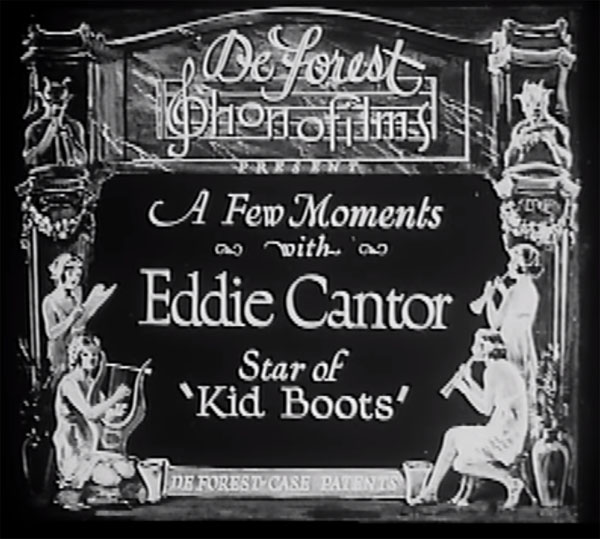

Phonofilms

and 'sound-on-film'

In the 1920's "Phonofilms"

were introduced by their inventors Theodore Case and Lee de Forest.

These moving picture shorts were intended to be something that could

be added to the featured movie bill. They were also seen as a novelty

by the public and by many in the silent film industry. The demonstrations

of sound-on-film technology in theatres are reminiscent of the first

demonstrations of Edison's tin-foil phonograph by travelling exhibitors

where paying audiences came to see and hear the new novelty and the

wonder of recorded sound.

The projection and sound

equipment for the Phonofilms had to be installed in a theatre and

few theatres or movie chains invested in permanent systems. A common

demonstration and distribution method, therefore, was for theatres

to have limited engagements, hence the travelling show analogy of

Edison's tin-foil entertainment device. De Forest explained that

"The "phono-film" is adapted

primarily for the reproduction of musical, vaudeville numbers and

solos...De Forest points out that his invention opens the way to scenics

carrying their own music, played by first class orchestras and comedies,

and animated cartoons with bright lines and patter." (Film

Daily, 7 April 1923, pp. 1-2)

For the story of Theodore

Case and the invention of the first commercially successful system

of sound-on-film and the demonstration of the Phonofilms, see the

"digital story-telling adventure" of Cayuga

Museum's Case Research Lab (called the Birthplace of Sound Film

where the Movietone sound-on-film

system was invented in the 1920's).

A 1923 sound-on-film demonstration

using the DeForest PhonoFilms of Eddie Cantor performing a

vaudeville routine can be seen and heard HERE.

WATCH

"A Few Moments with Eddie Cantor," 1923 DeForest Phonofilms

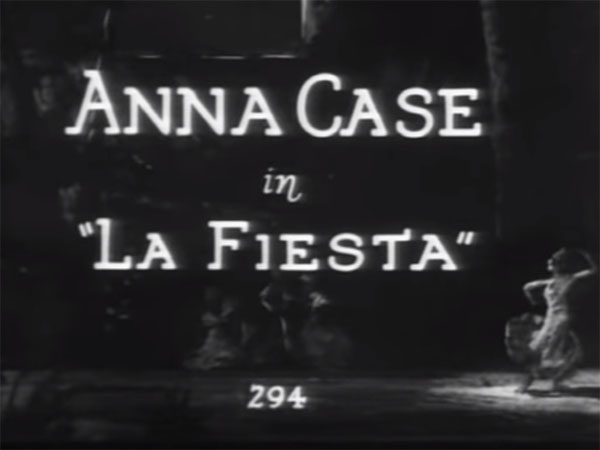

Anna

Case's Vitaphone film short "La Fiesta"

Anna Case, one of Edison's Tone

Test artists, made a moving picture for the 1915 advertising campaign

of the Edison Diamond Disc Phonograph at the time of Edison's "Voice

of the Violin' moving picture. Unfortunately, that Tone Test film

has been lost. There is, however, a later 1926

Metropolitan opera Vitaphone short (with sound) for "La Fiesta"

with Anna Case performing her song.

WATCH

Anna Case in this 1926 Vitaphone short for the film "La Fiesta."

Vitaphone Number 294, August 6, 1926.

On August 5, 1926 Warner

Bros. premiered their silent feature "Don Juan" which they

had updated with a symphonic musical score and sound effects. This

was "the first feature-length film to utilize the Vitaphone sound-on-disc

sound system with a synchronized musical score and sound effects,

though it has no spoken dialogue." (Wikipedia)

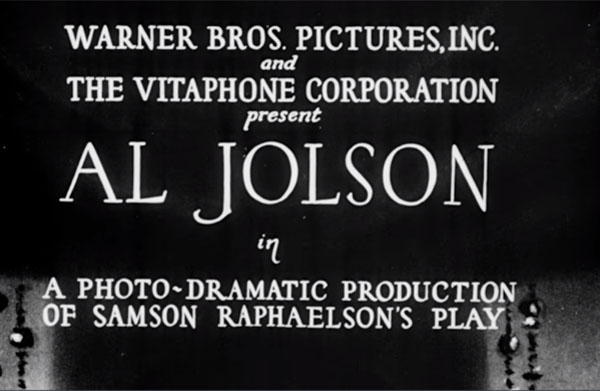

Vitaphone and "The

Jazz Singer"

"The Jazz Singer"

premiered on October 6, 1927 using The Vitaphone's sound-on-disc sound

system with a synchronized musical score and sound effects, but added

synchronized voice and songs. "The physical presentation of

the film itself was remarkably complex:

Each of Jolson's musical numbers

was mounted on a separate reel with a separate accompanying sound

disc. Even though the film was only eighty-nine minutes long...there

were fifteen reels and fifteen discs to manage, and the projectionist

had to be able to thread the film and cue up the Vitaphone records

very quickly. The least stumble, hesitation, or human error would

result in public and financial humiliation for the company. ( Eyman,

Scott, The Speed of Sound: Hollywood and the Talkie Revolution,

1926–1930. New York: Simon and Schuster. (1997), p. 140. - Wikipedia

With "The Jazz Singer's" popular

audience approval "1927

can be best remembered as the year of sound film, as two dueling systems

rushed to bring in the Talkie Era and dominate the entertainment industry.

For the duel between Movietone vs. Vitaphone see The

Sound Film Wars begin!" - Cayuga Museum.

"The Jazz Singer"

is commonly cited as the beginning of "the Talkies" and

the end of silent movies. As an event in popular culture "The

Talkies" had arrived.

One of the intertitles

providing dialogue for a scene in The Jazz Singer, 1927.

WATCH

The Jazz Singer

As seen by Gaumont's

Chronophone and Edison's Kinetophone, DeForest Phonofilms, Theodore

Case's Movietones, and others demonstrating moving pictures with sound,

The Jazz Singer wasn't the first movie to use recorded sound.

Likewise, The Jazz Singer still used some dialogue intertitles.

And as historian Richard Koszarski' has written, "Silent films

did not disappear overnight, nor did talking films immediately flood

the theaters...." (Koszarski, Richard (1994) [1990]. "An

Evening's Entertainment: The Age of the Silent Feature Picture, 1915–1928."

Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, p. 90).

The Vitaphone's system

of synchronized 'phonorecords' used physical records. But like Edison's

Kinetophone, using records and a mechanical system for playing records

had limitations and the Vitaphone was already being challenged by

other technologies like Movietone's sound-on-film.

By 1931 Vitaphone movies

were no longer being made. Interestingly, sound-on-disc for movies

did return with the 1993 movie "Jurassic Park" and "the

debut of the Digital Theater System (DTS), which stores the soundtrack

on a compact disc and uses a time code to synchronize itself to the

film. Unlike the Vitaphone phonograph record, the DTS compact disc

purportedly suffers no wear when played repeatedly. In a further continuation

of the format wars, DTS is rivalled by Dolby Systems’ AC-3, a digital

sound-on-film technology. ("Vitaphone

Vaudeville, 1926-1930." Essay by Richard Hildreth

for the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, Winter 2007.)

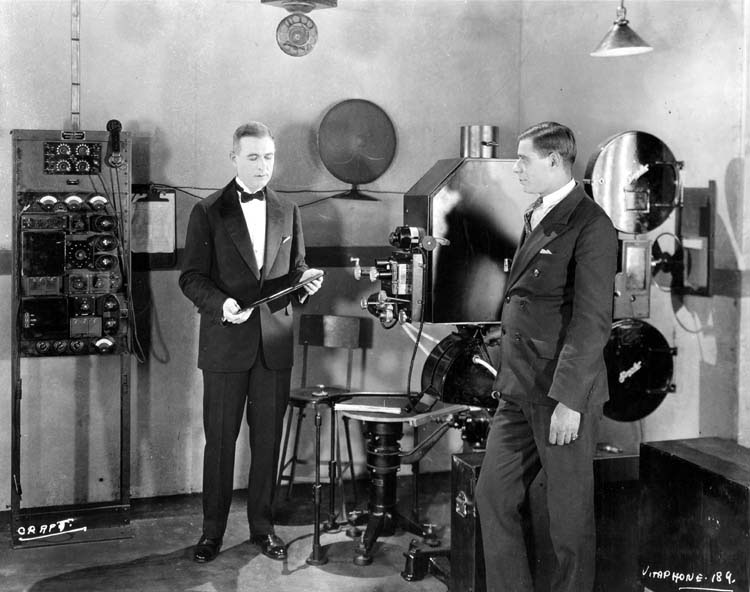

A Vitaphone projection

system was demonstrated in 1926. Engineer E. B. Craft holds a soundtrack

disc. The turntable, on a massive tripod base, is at lower center.

Wikipedia

Were Silent Movies Really

Silent?

As the many examples have

shown, The Jazz Singer, often called the first "talkie,"

was not the first film to synchronize with sound or to include spoken

dialogue. Also, as Rick Altman has documented, the idea is incorrect

that all previous movies before the 1927 The Jazz Singer were

"silent." Not only did many sounds accompany the 'silent

movies' a "variety of sound strategies" had been

used.

During the nickelodeon period

prior to 1910, this variety reached its zenith, with theaters often

deploying half a dozen competing sound strategies—from carnival-like

music in the street, automatic pianos at the rear of the theater,

and small orchestras in the pit to lecturers, synchronized sound

systems, and voices behind the screen. During this period, musical

accompaniment had not yet begun to support the story and its emotions

as it would in later years."

But in the 1910s, film sound acquiesced

to the demands of captains of the burgeoning cinema industry, who

successfully argued that accompaniment should enhance the film's

narrative and emotional content rather than score points by burlesquing

or "kidding" the film. The large theaters and blockbuster productions

of the mid-1910s provided a perfect crucible for new instruments,

new music-publication projects, and the development of a new style

of film music. From that moment on, film music would become an integral

part of the film rather than its adversary, and a new style of cinematic

sound would favor accompaniment that worked in concert with cinematic

storytelling. Source: Rick

Altman, Silent Film Sound, Columbia University Press, 2007

- Columbia

University Press Website

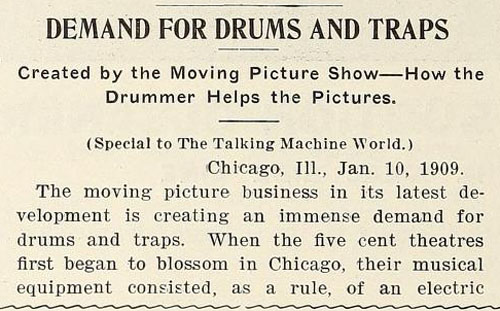

Drums and Pianos

The following 1909 article from the

trade magazine "The Talking Machine World" provides a timeline

for different "sound strategies" tried out by some movie

picture theatres - the player piano, the phonograph, live singers,

a real pianist, a four or five piece orchestra for the bigger theatres,

and when too expensive, back to simply a piano and drum.

"When the five cent theatres

first began to blossom in Chicago, their musical equipment consisted,

as a rule, of an electric piano, which kept things stirred up during

the intermission, and a talking machine which did the illustrated

song stunt."

But in the latest development the article

explains how there is now "an immense demand for drums and traps."

The advantages of having a drummer are

many: plenty of noise with imitations of various rough house stunts

depicted by the films, such as collapse of a building, the tumble

of a hero from the seventh story window, etc. The patter of a horse's

hoofs...the shuffling of feet...the squeak of a pig,

etc... "Practically all the shows are using the drummer as the

principal part of their equipment now and he keeps us wiring east

to keep up with the demand."

"How the

Drummer helps the Pictures," The Talking Machine World,

January 1909 (Disclaimer)

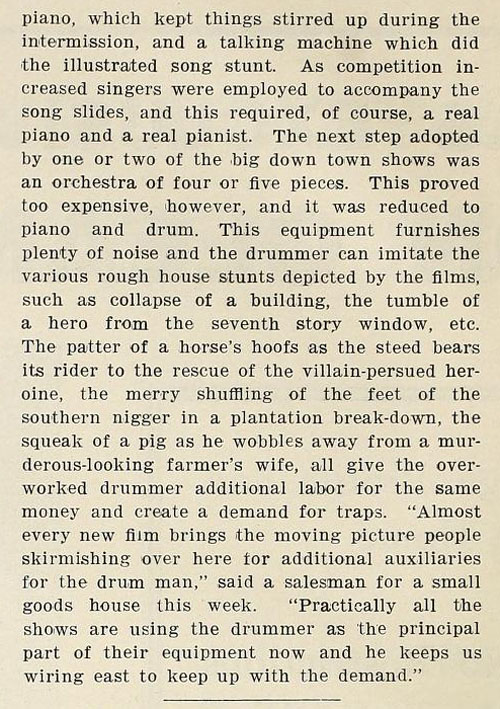

Pipe Organ used with

Biblical, mythological and historical subjects in movies.

Orpheum moving picture

theatre pipe organ, The Talking Machine World, April 1909

In the September 1915 issue of Photoplay's

"Close-Ups by Editor" section the following prediction was

made about the future of combining film and great music:

"I believe that "The Birth

of a Nation" is worth $2, and I believe that there will be other

screen plays worth $2 — perhaps... there will be wonderful combinations

of shadow-spectacle and master-music for which $5, or even more,

may be successfully asked."

Large and small orchestras, organs,

pianos, percussions and living voices provided most of the 'sound'

for the silent films.

The phonograph and its records, however,

have inserted into some movie scenes which is the focus of this Phonographia

gallery.

Phonographs in Movie

Houses

The following are examples

of movies where phonograph music was used in a movie house. Most of

these examples were the result of a local phonograph dealer providing

a phonograph and record related to a movie scene. Adding phonograph

sounds to theatre movies was viewed by the talking machine industry

and local phonograph dealers as an 'immense' advertising opportunity

in "wedding the talking machine" to the "movie theatre

and its program."

When there was a "wedding

of the talking machine" to the movie, however, it seems to have

involved an insertion or the stoppage of the film at the appropriate

(or in some cases "inappropriate) time in the movie in order

to play a phonograph record. That insertion wasn't always smoothly

done.

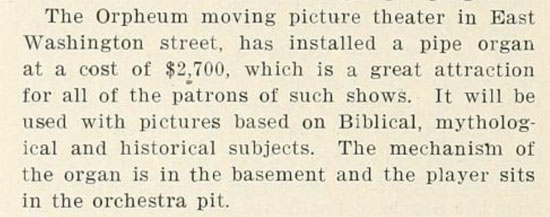

Talking Pictures with

the Phonograph humorously Out of Synch.

The Photoplay Magazine,

April 1915

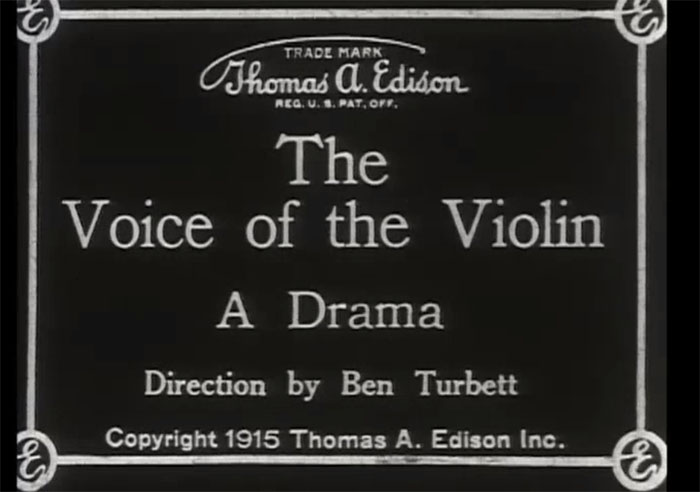

"The Voice of the

Violin" (1915)

The Thomas A. Edison movie,

The Voice of the Violin, was a silent film created to promote

the the Edison Diamond Disc Phonograph in 1915.

Two stars of the show were

the Edison Diamond Disc Louis XV Model B-375 Phonograph (1912 - 1915)

and the Edison Diamond Disc record "Feast of the Flowers."

This movie was intended to be used by Edison dealers and shown in

local theatres as an advertisement for the Edison Diamond Disc and

its "Re-created" music of the Edison Records. The violin

piece "Feast of the Flowers" was the featured Edison record

in the movie which was also surely played as part of the 'silent'

movie and was also important for its role in the story of reuniting

a family.

LISTEN

to "Feast of the Flowers" performed by American Symphony

Orchestra, Edison Diamond Disc Record 50118-R (Source: DAHR

and UCSB Library).

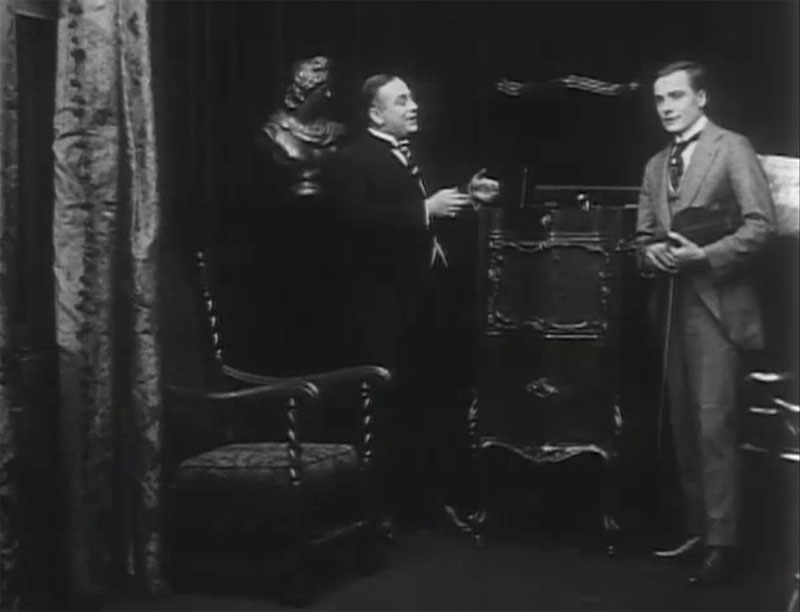

Listening to the

Edison Diamond Disc Louis XV Model A-375 Phonograph in "The

Voice of the Violin."

See Phonographia's "Voice

of the Violin" for more details about the movie, screenshots

from key scenes, and a link to the 20 minute movie which can be watched

courtesy of the Library

of Congress.

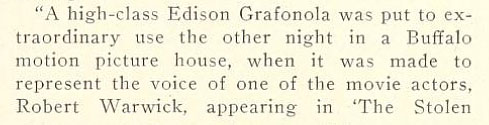

"The Stolen Voice."

(1916)

A "Victrola"

provided an "aria" and represented the voice of one of the

movie actors, Robert Warwick, in the silent 1916 movie "The

Stolen Voice."

The Talking Machine

World in 1916 reported seeing an article in a Chicago piano trade

publication which described a Buffalo, New York motion picture house

pausing the film so that a Victrola could quickly be moved into place,

and then restarting the film with the introduction of the talking

machine in the picture to which the "audience enthusiastically

applauded," an "aria from 'Pagliacci' was played and sung."

The Talking Machine

World, May 15, 1916

LISTEN

to the aria “Vesti la giubba,” sung by Enrico Caruso, Victor 12"

Red Seal Record 88061, recorded March 17, 1907 Giovannoni Collection

at the Library of Congress).

Note: The writer of this Talking

Machine World article had titled it "Can You Solve this

Puzzle? We Have Given Up," not because he was surprised

by a Victrola being used to provide the voice of one of the movies

actors. Instead, the puzzle was because there had been no

merger between Edison and Columbia (the maker of Garfonola's), and

there was no such machine as "a high-class Edison Grafonola."

To add further confusion, this phonograph was also later identified

as "the Victrola" (yet another company's machine).

TMW humorously answered the question

of why three makers of phonographs had been named: "Perhaps

it's an effort to be impartial, but in that case what about the

Pathe, the Sonora and a dozen others?" More likely, they

surmised, it was because the editor of the piano trade publication

was "careless in reading his clippings."

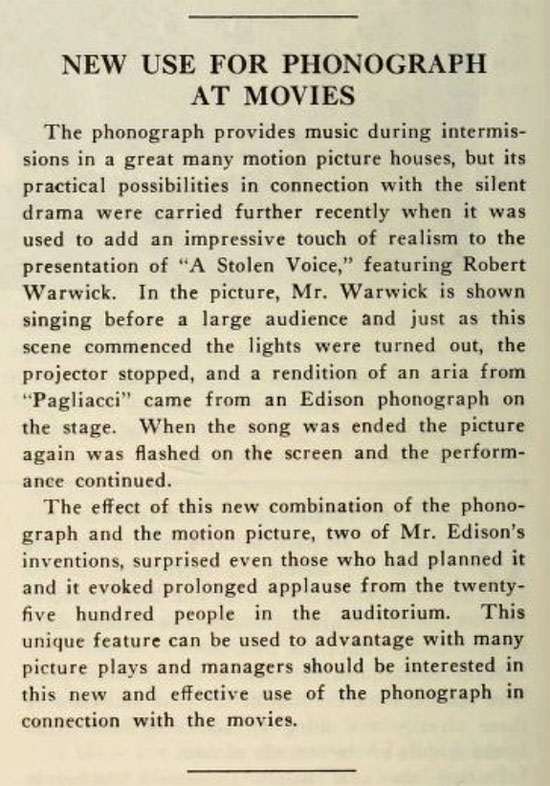

"A Stolen Voice. (1916)

The Edison Phonograph Monthly,

August 1916, provided more accurate details than were reported by

The Talking Machine World the previous month (see above) and

solved its "puzzle." In this presentation of "A Stolen

Voice," just as the scene commences where Mr. Warcik is shown

singing the lights were turned out, the projector stopped, and an

aria from "Pagliacci" came from an Edison phonograph on

the stage. When the song ended the picture again was flashed on the

screen and the performance continued."

It was then noted that this "new

combination of the phonograph and the motion picture" can

be "used to advantage with many picture plays and managers

should be interested in this new and effective use of the phonograph

in connection with the movies."

"The phonograph

provides music during intermissions in a great many motion pictures

houses..." The Edison Phonograph Monthly, August 1916.

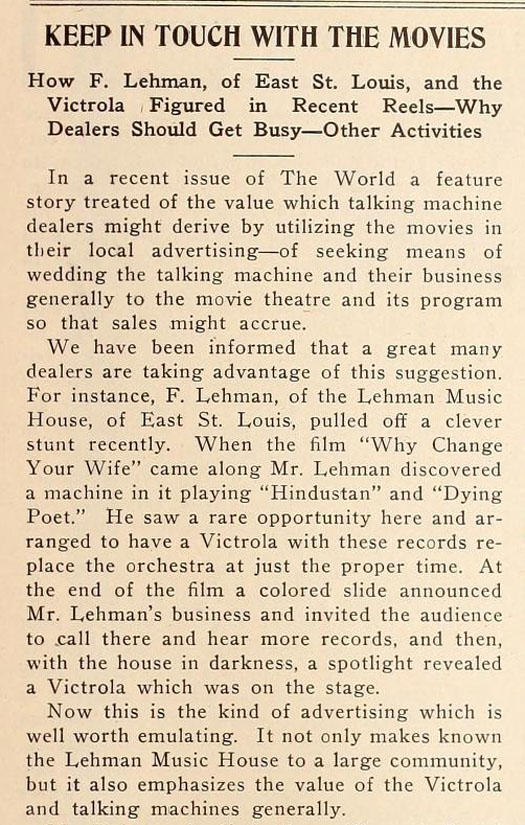

"Why Change

Your Wife." (1920)

- The movie insertion of the Victrola and two recorded songs.

The Talking Machine

World, June 15, 1920, p. 3.

The Lehman Music house

in St. Louis provided a Victrola and the Victor records "Hindustan"

and "Dying Poet" to a movie theatre after Mr. Lehman saw

the Cecil B. DeMille film "Why Change Your Wife." In that

film Lehman had seen a machine playing those songs and realized the

advertising opportunity he would have if he could replace the orchestra

at just the proper time with the Victrola music.

Screenshot of couple looking

at Victor Record 18623-A "Give Me a Smile and Kiss" and

then putting stylus onto the record player to their right. A close-up

of the Victor record is also shown in the movie.

LISTEN

to Victor 18623-A "Give me a smile and kiss" / John

Steel (Black label (popular) 10-in. double-faced) recorded on September

20, 1919 and released on September 29, 1919. (Source: DAHR Recording

from Library of Congress).

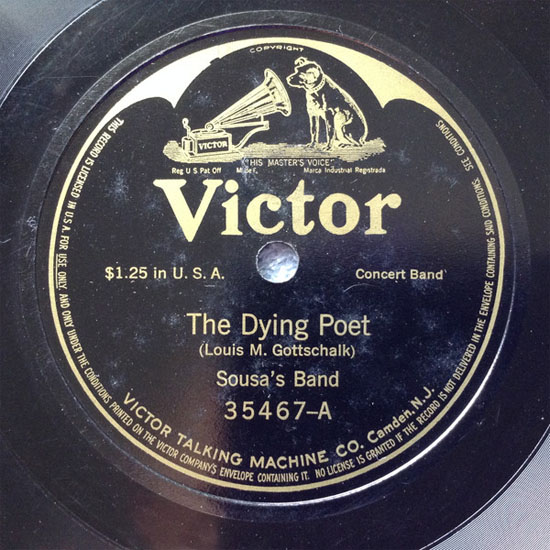

Screenshot of woman upset

with the record that was playing when she entered the room. She then

proceeded to break the Victor Record 35467-A "The Dying Poet""

in half.

LISTEN

to Victor Record 35467-A "The Dying Poet," Sousa's Band,

recording May 14, 1912 (Courtesy Library of Congress).

In another scene Victor

Record 18507-A "Hindustan" is shown for the audience to

read its title, and then it was played.

LISTEN

to Victor 18507-A "Hindustan" performed by Joseph C.

Smith's Orchestra, (Black label (popular) 10-in. double-faced) released

on July 17, 1918 (DAHR and Recording David Giovannoni Collection).

Lehman also created a colored

slide which invited the audience to visit his store and hear more

records. With the house in darkness, Lehman also arranged to have

a spotlight reveal a Victrola which was on the stage. "Now this

is the kind of advertising which is well worth emulating" noted

The Talking Machine World.

For other glass slides

being used for phonograph advertising in theatres, see Phonographia's

Movie

Slides Advertising the Phonograph.

"Many customers want

a record to remember the show. It is through the medium of the record

that they remember the show." The

Talking Machine World, December

15, 1920, pp.150,

152.

"The Barbarian."

(1921) and "Our Yesterdays."

A Sonora dealer provided

a Sonora Portable to a theatre to use in the movie "The Barbarian"

with the record "Our Yesterdays" to be played "at the

proper time", The Talking

Machine World, May 15, 1921.

LISTEN

to "Our Yesterdays" by Milton Charles played on Tivoli

Theatre Pipe Organ, Autograph Records, 4010-A, 1925. (David Giovannoni

Collection).

For an interesting story

about the desmise of the theatre movie organ after 1927 and the history

of one of those Wurlitzers which was saved, see The

Hardman Studio Wurlitzer The History of the Theatre Organ.

"Molly O"

(1922) and "Molly O."

Brunswick phonograph

in moving picture theatre, The Talking Machine World, March

15, 1922

"A Brunswick phonograph

was provided the the Brunswick Temple of Music store in connection

with the moving picture "Molly O," which was being featured

in the program. Several selections were played and before the picture

was flashed on the screen the well-known song record of the same name,

"Molly O," was played."

"Molly O (I Love You)"

Lyric by James C. Emery. Music by Norman McNeil, Waterson, Berlin

& Snyder Co., Music Publishers, New York, 1921 (Lester S. Levy Sheet

Music Collection, Johns Hopkins).

LISTEN

to "Molly-O (I Love You)" by William Robyn, Record 18829-A,

recorded 17Oct2021 (DAHR and Library of Congress).

"Honors Are Even"

(1923) - Victrola plays "La Golondrina

during one of the scenes..."

Victrola played "La

Golondrina" at the Toldeo Theatre during performance of "Honors

Are Even," The Talking Machine World, May 15, 1923. Note:

"Honors Are Even" opened on Broadway August 10, 1921, however,

no movie has been found.

LISTEN

to "La Golondrina" by Max Dolin Orchestra, Victor Record

73171-A, recorded November 22, 1921 (DAHR

- Recording UCSB).

Other

Factolas related to Music for the Movies

ENRICO CARUSO to become

film actor - "Attend a Caruso picture, with your phonograph

in your lap."

In Photoplay Magazine,

November 1915, there is an announcement that Enrico Caruso, the famous

tenor, is "to become a film actor... His first picture, from

the Pallas studios, will be Booth Tarkington’s “The Gentleman from

Indiana.” Arthur Johnson's argued that there are countless thousands

all over the world so eager for a sight of Caruso that his pantomime

will be welcome, even though the voix d’or is silent. Receipt for

an orgy: attend a Caruso picture, with your phonograph in your lap."

Geraldine Farrar uses

Bizet's music during the filming

of her movie "Carmen."

In Photoplay Magazine,

August 1915, Geraldine Farrar reported that Bizet's music would be

used while her new movie "Carmen" was being filmed. "When

my ‘Carmen’ film is taken at Lasky’s,” said she, “it will be to the

accompaniment of Bizet’s music... Bizet’s wonderful music makes me

a Russian or a Spaniard, whichever you will, above my belt. Without

it I am cramped, slow, heavy. So while the crank is inturning ‘Carmen,’

I’m going to have the music under way. I want you to see ‘Carmen’

in the bright shadows —not ‘Jerry’ Farrar. Understand?”

Film

Scores for Silent Films - The Library of Congress (its digital

collection includes over 3,000 items published or created for use

in silent film accompaniment between 1904 - 1927.)

The Music Division's

collection of music for silent film can be divided into four different

categories, the vast majority of which can be found under four different

call numbers. The four categories are:

Film Scores: written for specific

films, which can include full scores, piano scores, and sets of

orchestral parts

Cue sheets: served as musical primers

for film accompaniment, may or may not include music incipits

Photoplay albums: stock music written

specifically for use in accompanying silent film, which can include

piano scores and sets of parts

Salon orchestra music: music often

used in silent film accompaniment, but not originally published

with that use in mind, which primarily consists of sets of parts.

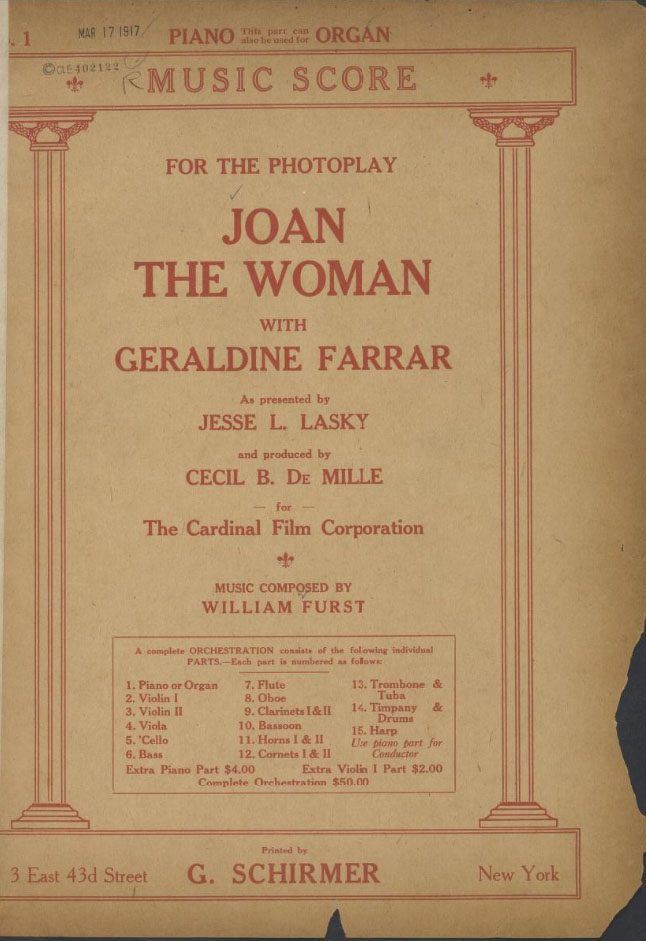

Music score for the photoplay

Joan the Woman with Geraldine Ferrar as presented by Jesse L.

Lasky and produced by Cecil B. De Mille for the Cardinal Film Corporation,

New York : G. Schirmer, [1917]. (Library of Congress: Silent Film

Scores and Arrangements).

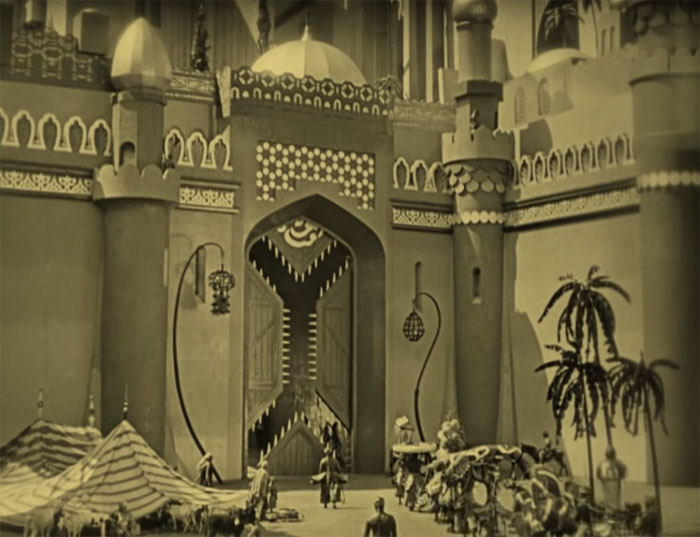

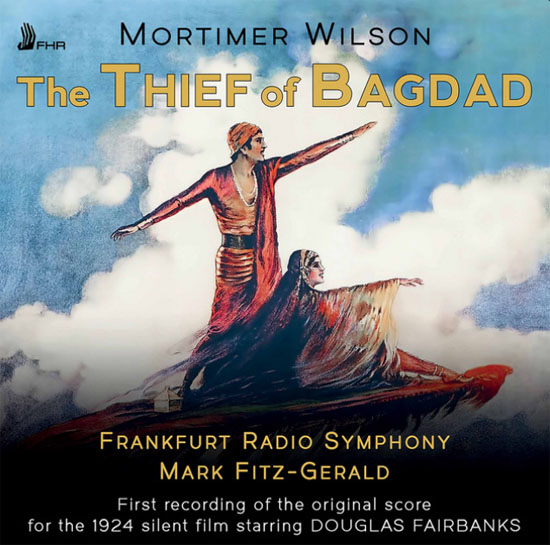

"The Thief of Bagdad"

As an example of a major

silent picture film score, the 1924 "The Thief of Bagdad"

starring Douglas Fairbanks has a Reconstructed

Film Score (from the original film score) which has been recorded

for the first time by the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra, Mark

Fitz-Gerald, First Hand Records ©2022 and can be heard on Spotify,

et al.

WATCH

the Thief of Bagdad Trailer from

Cohen Media Group

LISTEN

to the 1924 Thief of Bagdad (Spotify)

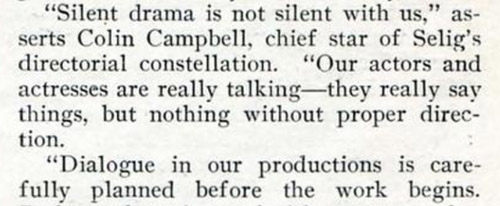

A Footnote on Silent

Movies: There is no "Silent" Drama.

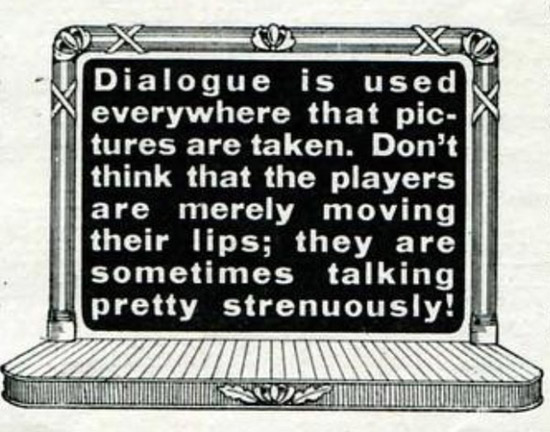

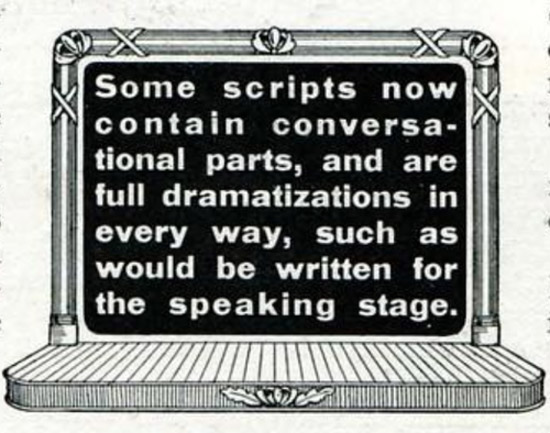

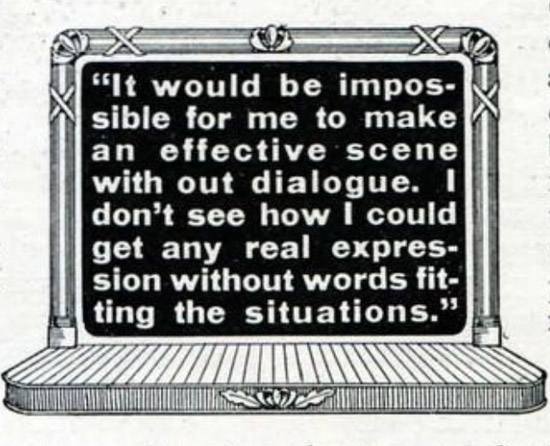

An article in Photoplay

Magazine, September 1915 starts with the question: Is "silent

drama" silent? If not, why, how and to what extent is it vocal?

Photoplay Magazine,

September 1915

The premise of this article

is that the actors are following scripts and are actually talking

-- and that the audience recognizes they are talking because of the

intertitles, the action and context of the scenes, and the words being

'spoken' by the actors in the movie. The article notes that "The

public is rapidly and unconsciously acquiring a very fair degree of

proficiency in lip-reading, and a false speech will be subconsciously

noted and resented, and the matter is of too great importance to depend

upon a chance selection of words."

"During the early days of picturemaking

little attention was paid to dialogue, with the result that the

action lost much of its meaning and continuity. It wandered. Frequently

nonsense or profanity was introduced."

Dialogue, it was being

said, was used in silent movies and that meant they weren't really

"silent."

Perhaps Photoplay's

further example could have been that seeing dialogue in silent movies

was like reading a book, with the voices in each case being "heard"

in the mind -- either by reading the dialogue in the context of the

book's story or by reading the lips, intertitles, and emotions/action

in the movie.

The following are some

of Photoplay Magazine's conclusions regarding dialogue being

used in the "no silent" movies of 1915:

Photoplay Magazine,

September 1915, pp. 73-76

Movie

related songs and performances pre-1929.

"At

the Movies" by Ethel C. Olson, Victor 10" Ethnic Norwegian

Series 77251, Comic Monologue, recorded November 6, 1923 (David Giovannoni

Collection, i78s.org).

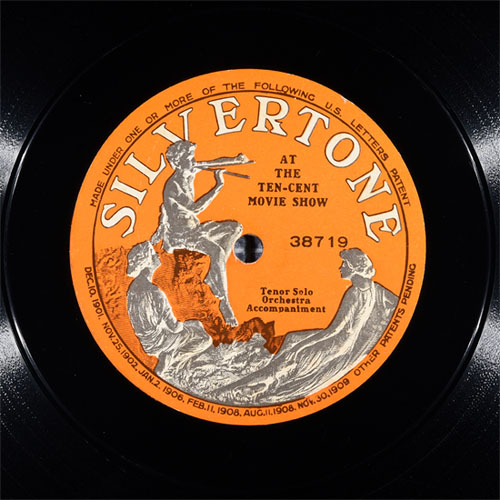

At

the Ten-Cent Movie Show by Walter Van Brunt, Silvertone 10"

Record 38719 (Columbia Client), recorded on March 21, 1913. (Ibid.)

"Echoes

from the Movies" Accordian played by Pietro J. Frosini, Edison

Blue Amberol, Record 2531, recorded October 31, 1914. (Ibid.)

"Ever

Since the Movies Learned to Talk" from Whoopee by Billy Murray,

Harmony 10" 784-H, recorded November 15, 1928 (Ryan Barna Collection,

i78s.org).

"He's

working in the movies now" by Billy Murray, Edison Record

2335, 4-minute celluloid cylinder, recorded March 27, 1914 (David

Giovannoni Collection).

"Since

Mother Goes to the Movie Shows" by Billy Murray, Edison Blue

Amberol, Record 2920, recorded February 3, 1916 (EPM New Releases

for August 1916). (Ibid.)

The following are a few

examples of recorded music that have become well-known by being associated

with respective movies.

Best Selling Soundtrack Albums

(as of January 1, 2023) - See Wikipedia

for latest lists.

1992 The Bodyguard

by Whitney Houston & Various

1977 Saturday Night

Fever, by Bee Gees & Various

1987 Dirty Dancing

by Various

1997 Titanic: Music

from the Motion Picture by James Horner & Various

1978 Grease: The Original

Soundtrack from the Motion Picture by Various

Best Streaming Soundtrack

Albums (as of January 1, 2023) - See Wikipedia

for latest lists.

2015 Furious 7 ("See

You Again") by Wiz Khalifa, Charlie Puth

2018 A Star Is Born

by Lady Gaga, Bradley Cooper

2017 The Greatest Showman

by Hugh Jackman, Keala Settle, Zac Efron, Zendaya, Various

2013 Frozen ("Let

It Go") by Robert Lopez, Kristen Anderson-Lopez, Idina Menzel, Kristen

Bell

2016 Moana by Lin-Manuel

Miranda, Mark Mancina, Opetaia Foa'i, Auli'i Cravalho, Alessia Cara

For examples of popular

Movie Songs identified in 2022, see Best

Movie Songs - 50 Themes from Hollywood Film Classics.

A Friend of the Phonograph's

memories of sound track record albums.

Growing up in the 1950's and 1960's

our family saw several movies at the Omaha Cinerama (where souvenirs

and memorabilia for some of the movies were also sold). Two albums

that my parents purchased because of going to the movies were Michael

Todd's "Around the World in 80 Days" in Todd-AO and "How

the West Was Won."

Our movie soundtrack LP library

also included "The Great Race" and "The Sound of

Music." (DB,

2004)

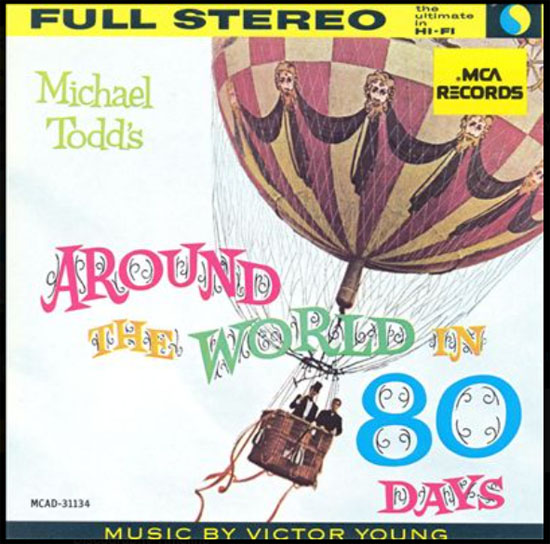

"Around the World

in 80 Days," MCA Records, 1956

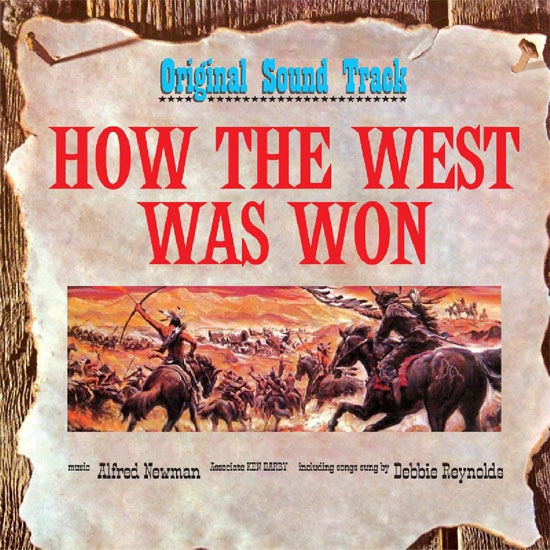

"How the West Was

Won," Original Sound Track, MGM Records, 1963

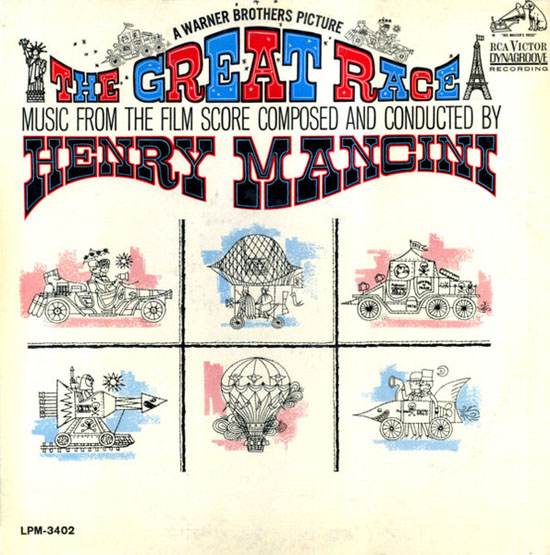

"The Great Race,"

RCA Victor Dynagroove Recording, Music from the Film Score, 1965

"The Sound of Music,"

RCA Victor Stereo, An Original Soundtrack Recording, 1965

Sound Recordings - Copyright

Registration for Sound Recordings -- (Copywrite

Office Circular 56 Revised

03/2021 - Copyright.gov)

Sound Recordings Distinguished

from the Sounds Accompanying a Motion Picture

There is a legal distinction

between a sound recording and the soundtrack for a motion picture

or other audiovisual work. The Copyright Act states that “sounds accompanying

a motion picture or audiovisual work” are not sound recordings. These

types of sounds are considered part of the motion picture or audiovisual

work. Common examples of works that do not qualify as sound recordings

include:

• The soundtrack for a cartoon, documentary,

or major motion picture.

• The soundtrack for an online video,

music video, or concert video.

• A

musical performance during a scene or during the credits for a motion

picture.

Sound Recordings Distinguished

from Phonorecords A sound recording is not the same as a phonorecord.

A phonorecord is the statutory term for a physical object that contains

a sound recording, such as a digital audio file, a compact disc, or

an LP. The term “phonorecord” includes any type of object that may

be used to store a sound recording, including digital formats such

as .mp3 and .wav files.

Sound Recordings Distinguished

from Phonorecords

A sound recording is not

the same as a phonorecord. A phonorecord is the statutory term for

a physical object that contains a sound recording, such as a digital

audio file, a compact disc, or an LP. The term “phonorecord” includes

any type of object that may be used to store a sound recording, including

digital formats such as .mp3 and .wav files.

Movie

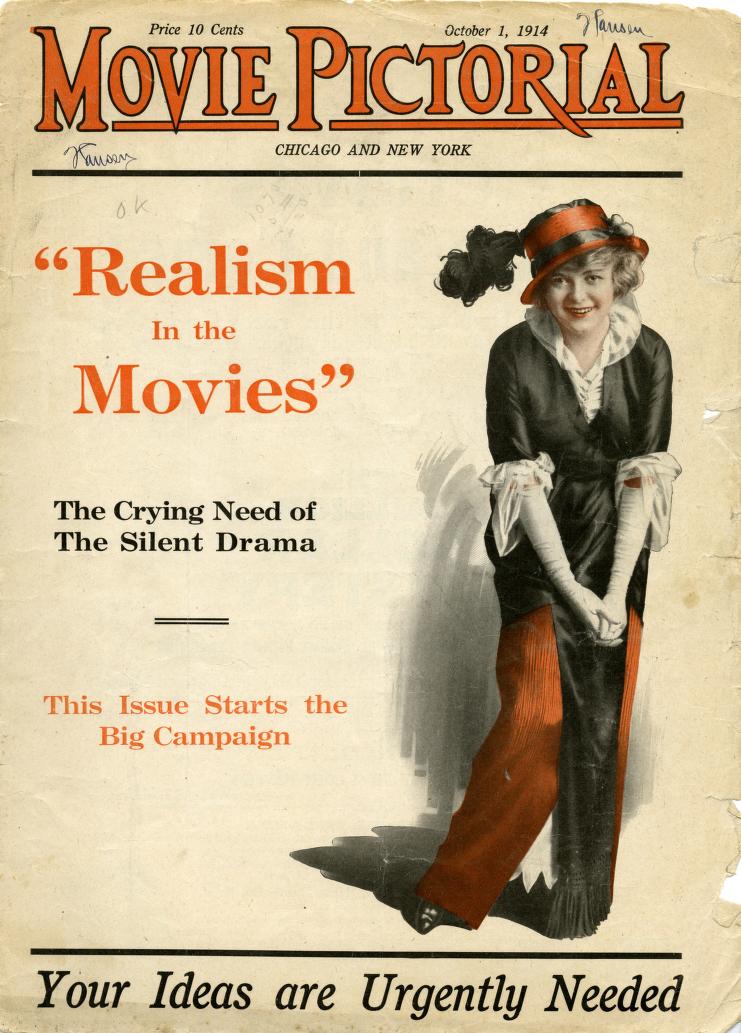

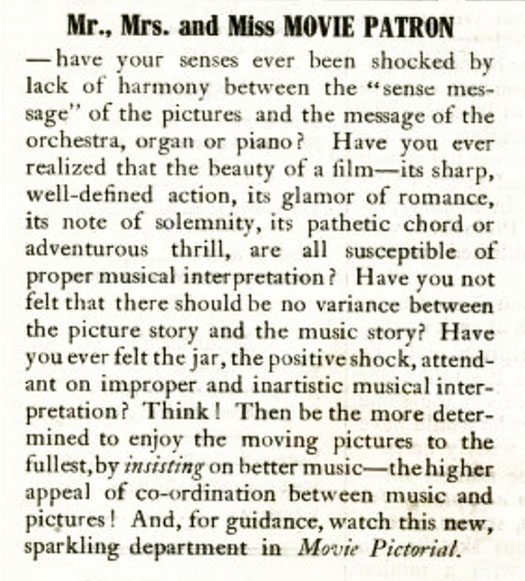

Pictorial Magazine, October 1, 1914 - "The

Crying Need of The Silent Drama"

Movie Pictorial,

October 1, 1914

Movie Pictorial's

New Department - THE MUSIC STORY - A Department for

Musical Interpretation of Moving Pictures

The Lack of Harmony

between the visual messages and music messages of the movie

Movie patrons must insisting

on better music "to enjoy moving pictures to the fullest"

and higher co-ordination between music and pictures! "How to

Make Music Tell the Story of the Films, Movie Pictorial,

October 1, 1914

Film

Players Herald Tradelasts

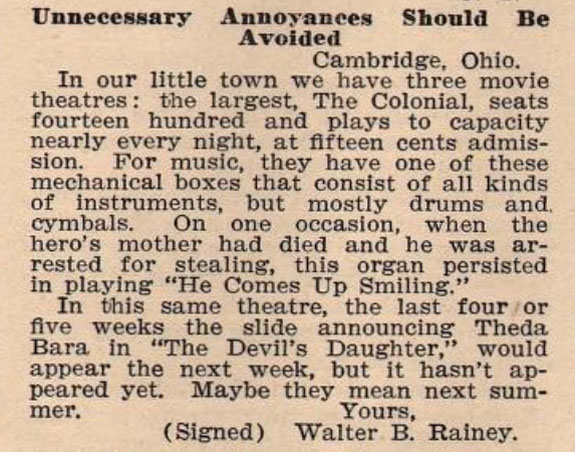

"Things About My Theatre I Like and Dislike"

Disconnects Between

Movies and their Music

"Mechanical boxes

for music" plays inappropriate song. Film Players Herald,

February 1916

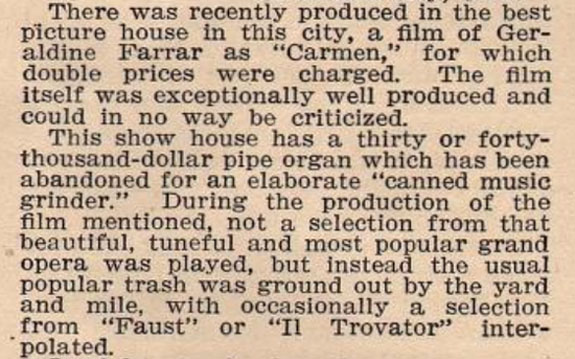

"Canned music grinder"

is inexcusable for "Carmen and Geraldine Farrar's film as "Carmen."

Geraldine Farrar

as "Carmen." Film

Players Herald, February 1, 1916

Resources

This gallery is a very

limited scrapbook of the history of silent and talking movies, soundtracks,

and other movie connections with the phonograph and recorded sound.

For a comprehensive examination with wonderful illustrations related

to "all aspects of sound practices during the silent film period

in America" see Rick Altman's "Silent Film Sound,"

Columbia University Press, 2004.

For more details on Phonofilms

and MovieTone's sound-on-film system see Cayuga

Museum of History & Art: "Inventing the 20's: Recording Sound

on Film." Also see,

Encyclopedia.com's "Virtual

Broadway, Virtual Orchestra: De Forest And Vitaphone."

For a list of movies where

phonographs appeared in a movie, see Phonographia's

Phonographs in the Movies.

For examples of video game

soundtracks on LPs, see Phonographia's "Video

Game Soundtracks."

For a May 2024 sampling

of The New York Time's readers favorite soundtracks, see "Hundreds

of Readers Told Us Their Favorite Soundtracks. Which Came Out on Top?"