The World's Columbian

Exposition of 1893 and the Kinetograph

By Doug Boilesen,

2021

The Kinetograph

When the World's Columbian Exposition

published their Official

Guide of the World's Columbian Exhibition (before the fair

opened) it wrote "among the most unique exhibits is the new

kimetograph (sic) [kinetograph]."

Official Guide of

the World's Columbian Exhibition, 1893

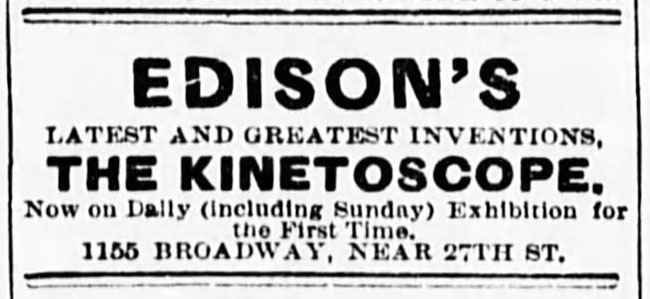

On October 17, 1888 Edison had filed

a caveat with the Patents Office "describing his ideas for

a device which would "do for the eye what the phonograph does

for the ear" -- record and reproduce objects in motion. Edison

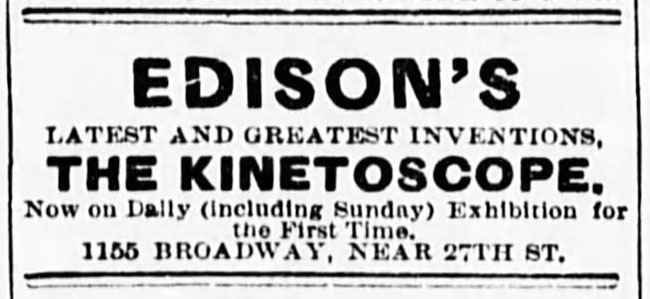

called the invention a "Kinetoscope," using the Greek words "kineto"

meaning "movement" and "scopos" meaning "to watch." A patent for

the Kinetograph (the camera) and the Kinetoscope (the viewer) was

filed on August 24, 1891. See kinetoscope

at Loc.gov.

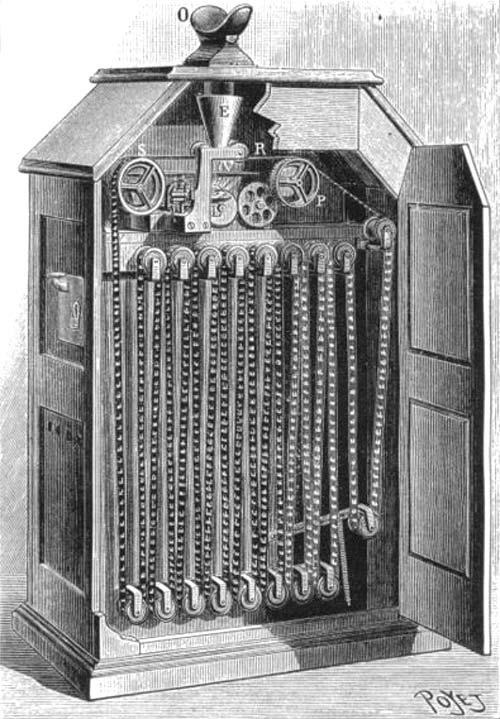

The Prototype Kinetoscope

"On May 20, 1891, the first

public demonstration of the prototype Kinetoscope was given

at the laboratory for approximately 150 members of the National

Federation of Women's Clubs. The New York Sun described what

the club women saw in the "small pine box" they encountered: In

the top of the box was a hole perhaps an inch in diameter. As they

looked through the hole they saw the picture of a man. It was a

most marvelous picture. It bowed and smiled and waved its hands

and took off its hat with the most perfect naturalness and grace.

Every motion was perfect....(2).

The

Aurora News-Register, Aurora, Nebraska July 18, 1891

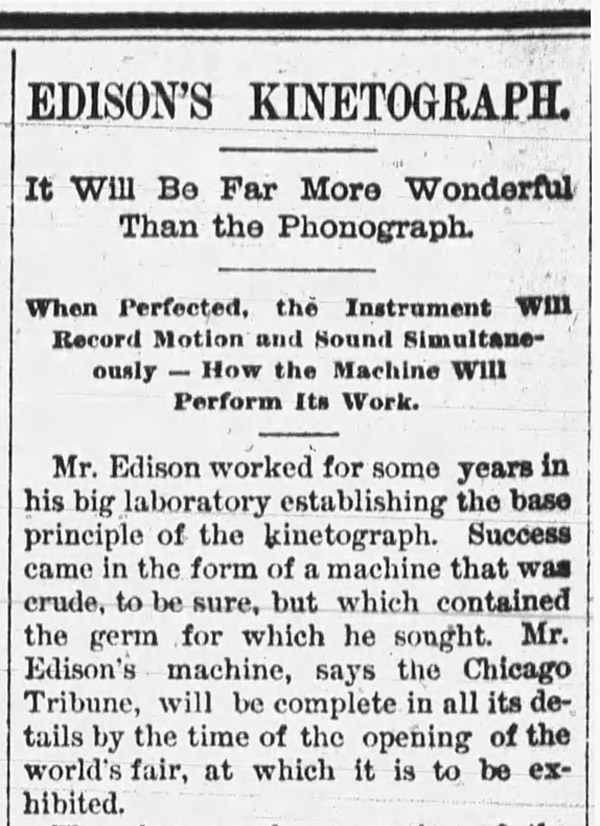

"I think we'll have

the kinetograph through in time for the World's Fair," said

the inventor. "That's what I am working on it for."

Chicago

Tribune, October 7, 1891

The Kinetograph's

First Public Demonstration

The kinetograph was first publicly

displayed on May 9, 1893 at the Department of Physics of the Brooklyn

Institute. Scientific American reported this event in their

May 20, 1893 edition saying that "the members were

enabled, through the courtesy of Mr. Edison, to examine the new

instrument known as the kinetograph." (1)

"The instrument

in its complete form consists of an optical lantern,

a mechanical device by which a moving image is projected

on the screen simultaneously with the production

by a phonograph of the words or song which accompany

the movements pictured. For example, the photograph

of a prima donna would be shown on the screen, with

the movements of the lips, the head, and the body,

together with the changes of facial expression,

while the phonograph would produce the song; but

to arrange this apparatus for exhibition for a single

evening was impracticable. Therefore, a small instrument

designed for individual observation, and which simply

shows the movements without the accompanying words,

was shown to the members and their friends who were

present."

"After projecting

upon the screen a few sections of the kinetograph

strip, the audience—which consisted of more than

400 scientific people— was allowed to pass by the

instrument, each person taking a view of the moving

picture, which averaged for each person about half

a minute. The picture represented a blacksmith and

two helpers forging a piece of iron...."

"The machine in

this case was not accompanied by the phonograph, but nevertheless

the exhibition was one of great interest. The kinetograph

in this form is designed as a "nickel in the slot" machine,

and a number of them have been made for use at the Columbian

Exhibition at Chicago."

The May 9 'kinetograph' was

defined in all reports as the device that included sound from

a phonograph that could synchronize the viewed movements and

lips of the moving photographs with sounds from the phonograph.

For that first public demonstration of that kinetograph, however,

the phonograph was not connected. At the end of the lecture

and demonstration the audience looked into the kinetoscope's

peep-hole viewer, each person watching a blacksmith scene

moving picture for less than 30 seconds.

Film

historian Charles Musser summarized the audience viewing

the kinetoscope film after George M. Hopkins finished his

lecture at the premier of Edison's new motion picture system,

the kinetoscope and kinetograph camera on May 9, 1893 as follows:

"When

the lecture concluded, at least two twenty-second films were

shown: BLACKSMITHING SCENE and HORSE SHOEING. Four hundred

people in attendance lined up in front of Edison's peep-hole

kinetoscope and one by one looked in the viewer and saw one

of these two films."

The May 20,1893 Scientific

American article concluded "The kinetograph in

this form is designed as a "nickel in the slot" machine, and

a number of them have been made for use at the Columbian Exhibition

at Chicago." This coin-operated kinetograph would

be known as the kinetoscope.

The Standard

Union, Brooklyn, May 10, 1893 reporting on the kinetograph's

first public demonstration

Going to

the Chicago and the World's Columbian Exhibition

The Ottawa Daily Citizen

reported in March 1893 that one hundred and fifty kinetographs

with moving pictures and sound will be at the World's Columbian

Exposition. The kinetograph will be an enclosed device with

a nickel in the slot mechanism that is coin activated. The

writer said that Edison "ought to make a fortune"

from his one hundred and fifty kinetographs at the fair.

"going

to Chicago...as a penny-in-the-slot machine."

The Standard

Union, Brooklyn, May 10, 1893

Following the kinetograph's

first public display in Brooklyn The Standard Union said

that it "was going to Chicago, there to be exhibited in

the Fair grounds as a penny-in-the-slot machine."

"Edison

will lead the procession this summer at Chicago with "perhaps

greatest of his inventions, the kinetograph."

The Edison Kinetograph was an instrument

intended "to reproduce motion and sound simultaneously, being

a combination of a specially constructed camera and phonograph."

The kinetograph is a "combination photograph and phonograph"

explained the 1892 Historical

World's Columbian Exposition and Chicago Guide giving fair

visitors advance information on what they would be able to see.

The Phonogram,

October, 1892, p. 217

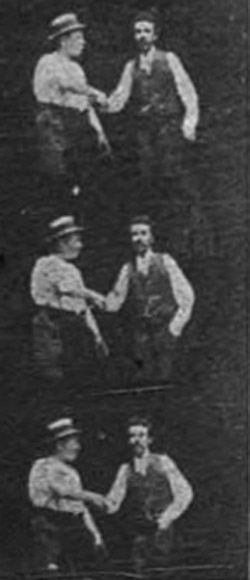

William K. Dickson and

William Heise, his associate and fellow filmmaker shake hands in

this kinetograph film,

The Phonogram, October 1892, p. 220.

The phonograph trade

magazine The Phonogram in their March-April 1893 issue noted

that "the famous Edison kinetograph" would be exhibited

in the Machinery Hall "under Class H, its proper classification."

The Phonogram,

March and April, 1893

"The Kinetograph

To Be the Individual Exhibit of the Great Inventor

At the World's Fair"

The differention between

the kinetograph and kinetoscope was clarified by Edison

in an April 1893 interview (The Indianapolis News,

April 27, 1893). "The kinetograph," he said,

"or, to put it more explicitly, the kinetoscope,

is a very simple device." Details followed but

it was all under a headline which emphasized that

"the Kinetograph was to be the Individual Exhibit

of the Great Inventory at the World's Fair..."

The

Indianapolis News,

April 27, 1893 p. 5

Additional information

was provided in an April 27, 1893 of the Indianapolis

News which noted that the "first perfected

kinetoscope which is a domestic kinetograph was finished

in the Edison laboratory at Orange, N.J., a few weeks

ago. Besides the kinetoscopes in the World's Fair

150 will be placed around the city. The kinetograph

will be displayed in some hall in the business center.

This feature of the Edison exhibits is part of the

display of the phonograph company in the southwest

gallery of the Electricity Building." This

would mean that the kinetograph exhibit was intended

to be part of the phonograph exhibit and that the

kinetoscopes as coin-operated devices would be in

other areas of the fair grounds and around the city.

The Indianapolis

News, April 27, 1893 p. 5

The

Alton Weekly Telegraph,

July 13, 1893 titled "The Kinetograph

and Kinetoscope" wrote that when Edison's nickel-in-the-slot

instrument is without the phonograph it is called

the kinetoscope but when a phonograph is

attached, "giving the sounds of the hammer

as well as the talking of the men" the instrument

is called the kinetograph." The "giving

the sounds of the hammer" was referring to

the Edison film "The Blacksmith Scene"

which was to have accompanied the film with phonograph

recorded sounds at the Brooklyn demonstration. That

first public display of the kinetograph on May 9

showed Edison's film "the blacksmith scene,"

however, it did not have sound as the phonograph

was not connected for that demonstration.

Was the Kinetograph at the World's

Fair in Chicago?

Over the years some film and other

historians have had different opinions about whether or not the

kinetograph was exhibited by Edison at the World's Columbian Exhibition

of 1893.

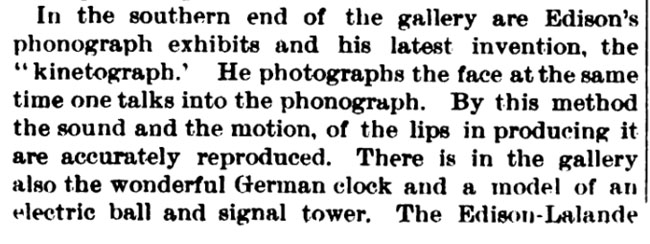

Scientific American,

October 21, 1893 reported that the kinetograph is "in the southern

end of the gallery" and that article has been cited as evidence

that there was at least one kinetograph as the fair.

Scientific American,

"Notes from the Worlds Columbian Exposition,"

October 21, 1893

The October 21, 1893

"Scientific American Notes" from the fair, however,

reads more like the description of a process than the actual watching

of moving pictures with sound.

"He photographs the face

at the same time one talks into the phonograph. By this method

the sound and motion, of the lips in producing it are accurately

reproduced."

Describing the process of making a

moving picture by photographing the face and recording the voice

at the same time on a phonograph was a common sentence included

in many newspapers about the kinetograph prior to the fair opening.

Likewise, newspapers often repeated

metaphors and similes to explain what the kinetograph does, e.g.,

the kinetograph "transmits scenes to the eye as well as sounds

to the ear;" and "it is to the eye what the phonograph

is to the ear."

This "process" description

by Scientific American on October 21, 1893, however, is insufficient

evidence that there was a kinetograph being exhibited at the fair.

Descriptions from the pre-fair newspaper articles and promotions

about the kinetograph going to Chicago are not evidence that anyone

actually saw the kinetograph at the fair. When the kinetograph was

first publicly displayed on May 9, 1893 at the Department of Physics

in Brooklyn before over 400 scientific people "the exhibition

was one of great interest" and there were details of what

was seen even though those moving pictures weren't accompanied by

the phonograph. "But even in this form it was startling in

its realism and beautiful in the perfection of its workings"

wrote the Standard

Union, May 10, 1893.

Therefore, where are any reports during

the fair about seeing the kinetograph and finding it "of great

interest?" Where is any sense of wonder, "the startling

realism," or the "perfection of its workings" portrayed

in this Scientific American article or any other newspaper

while the fair was open?

Newspaper articles that go beyond

the pre-fair explanations about the kinetograph and instead speak

of it as something being seen on exhibit at the fair are absent

during the entire time the World's Columbian Exposition was open.

The April 27, 1893 newspaper article

by Norton, Kansas's The Champion was written before the fair

was open and we know that it was mistaken in saying that the "kinetographs

had already been shipped to the fair."

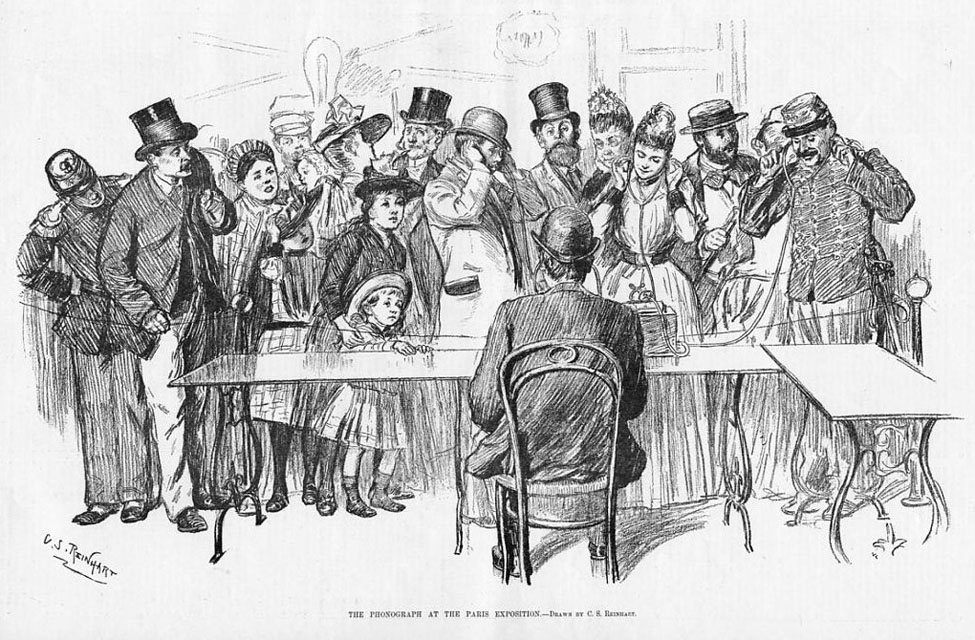

What The Champion

did get right, however, was their anticipation that delivery of kinetographs

should "excite the admiration of the world no less than the phonographs

at Paris."

Visitors at the Paris Exposition

Listening to Edison's Phonograph, Harper's Weekly, illustration

by C. S. Reinhart, 1889

The Kinetograph was not at the World's

Fair

In her book Six Months at the World's

Fair by Mrs. Mark Stevens published in 1895 she says she tried

to cover as much of the fair as possible so that she could then accompany

the reader "over the ground from one p;oint of interest to another."

In visiting the phonographs in the Electricity

Building she went into some detail about how the sound of the music

would change when the speed changed. She remarked that since the Fair,

Edison has "made important improvements upon this instrument.

His kinetograph at the time of the Fair was not perfected, but we

presume that long ago it has been...This instrument was not at the

World's Fair, as he then was working upon an apparatus sufficiently

large to produce this very thing."

Six Months at the

World's Fair by Mrs. Mark Stevens, The Detroit Free Press Printing

Company, ©1895, p. 231.

;

Where was the sense of wonder and

admiration by the public at the fair for the kinetograph?

This lack of reporting reactions from

first-time viewers about seeing the kinetograph at the fair is counter

to the history of the public seeing such inventions for the first

time. The admiration the Parisian visitors gave to Edison's phonographs

in 1889 is an obvious example of enthusiasm and curiosity for a

new wonder. Even after the phonograph's coin-in-the-slot machines

had been introduced to the public in 1889 there would continue to

be many examples of the public listening to coin-operated phonographs

for the first time and finding it a delight and curious about what

was inside the box. Jokes were still being circulated in the first

decade of the twentieth century about listeners being confused by

the phonograph's realism and questioning the source of those sounds

("Where's the Band?"

humor).

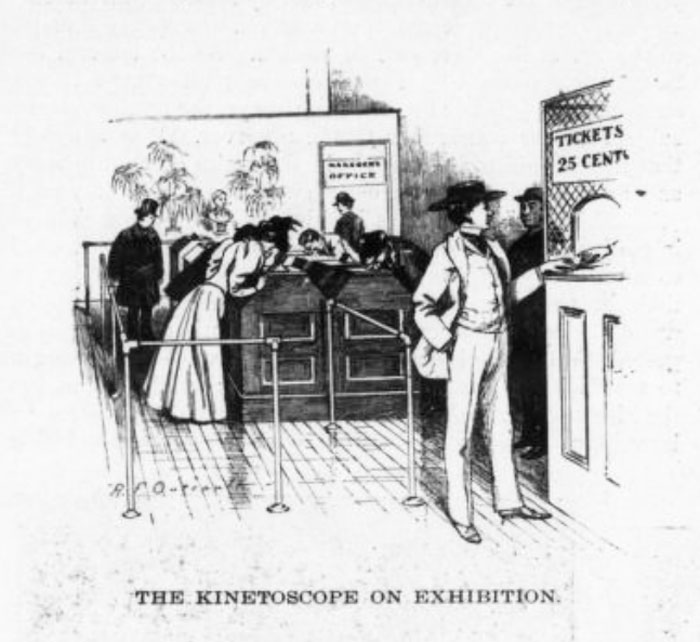

When the first kinetoscope parlor

in New York City opened in April of 1894 six months after the fair

closed there was much public interest. Terry Ramsaye wrote the following

in his book "A Million and One Nights - A History of the

Motion Picture." (4)

"Holland Brothers's Kinetoscope

Parlor offering "the Wizard's latest invention" was

a Broadway sensation. Long cues of patrons stood waiting to look

into the peep hole machines and see the pictures that lived and

moved."

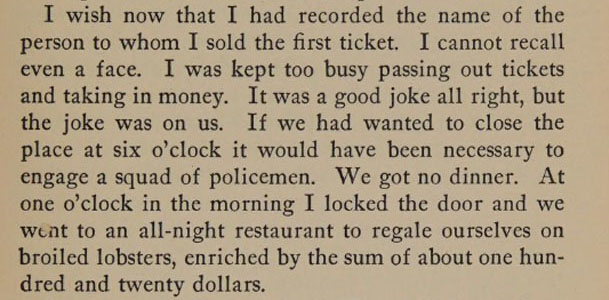

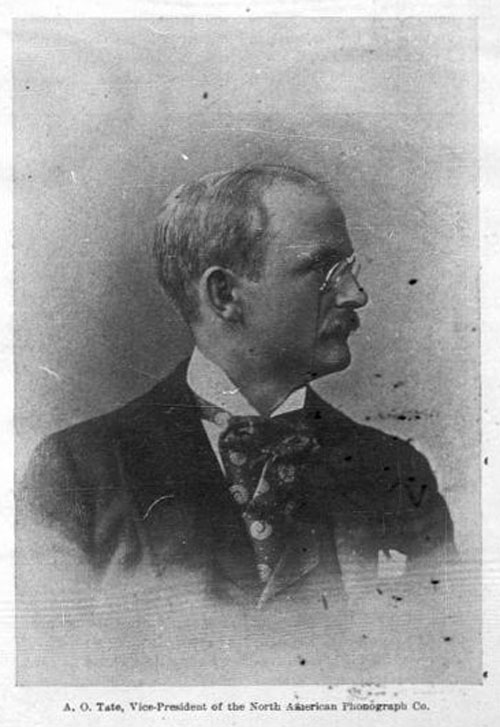

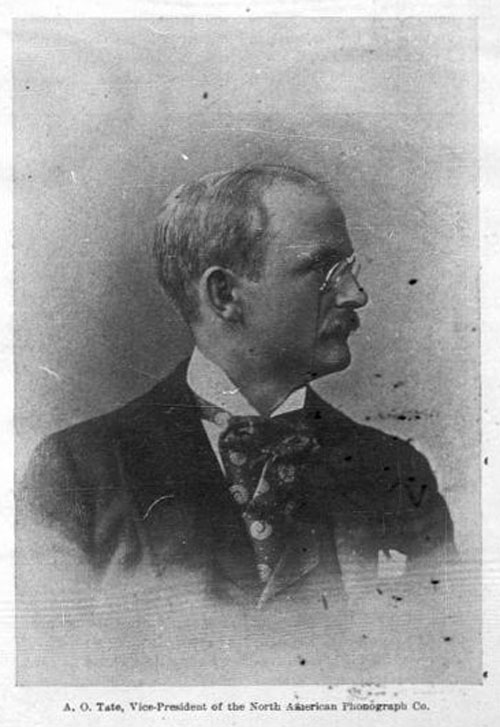

A first-hand report by Alfred O. Tate

of the Kinetoscope Parlor's opening night at 1155 Broadway provides

the best description of the enthusiasm of the crowd when Tate describes

how busy he was from the first ticket he sold until he locked the

door that night at one o'clock in the morning. "If we had wanted

to close the place at six o'clock it would have been necessary to

engage a squad of policemen."

Alfred O. Tate, "Edison's

Open Door - The Life Story of Thomas A. Edison A Great Individualist,"

(New York, E.P. Dutton & Co., 1938), 287.

There are no similiar

reports or evidence that anyone saw the kinetograph's moving pictures

or viewed a film through a kinetoscope at the World's Fair.

No kinetoscope, no synchronized

sound and no Edison films shown at the fair

Even if one kinetograph was delivered

and in "the southern end of the gallery" it would not

have been a functioning kinetograph connected to a phonograph providing

synchronized sound. The device that could display the "motion

of the lips" and the sound from those lips to be "accurately"

reproduced was still being developed and not available until 1895

when it came out as a kinetophone (the kinetophone being a combination

phonograph and kinetoscope). Dickson wrote in 1894 that "the

establishment of harmonious relations between kinetograph and phonograph

was a harrowing task... but "the experiments have borne their

legitimate fruit, and the most scrupulous nicety of adjustment has

been achieved, with the resultant effects of realistic life, audibly

and visually expressed." (8)

According to historian David Robinson"The

Kinetophone...made no attempt at synchronization. The viewer listened

through tubes to a phonograph concealed in the cabinet and performing

approximately appropriate music or other sound." Historian Douglas

Gomery concurs, "[Edison] did not try to synchronize sound and

image." (See Wikipedia's

kinetoscope and 'section "kinetophone"

for Robinson and Gomery quotes extracted 2-1-2022).

Terry Ramsaye, author of the 1926

"A Million and One Nights - A History of the Motion Picture"

did extensive research regarding the history of the kinetograph

and kinetoscope and interviewed many who were part of the film industry

from its beginning.

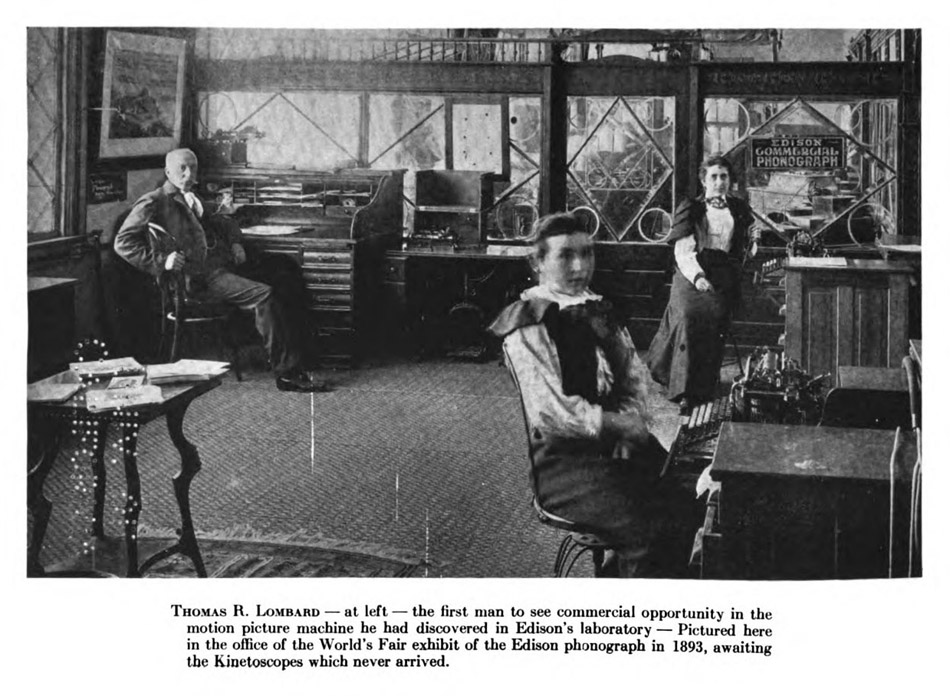

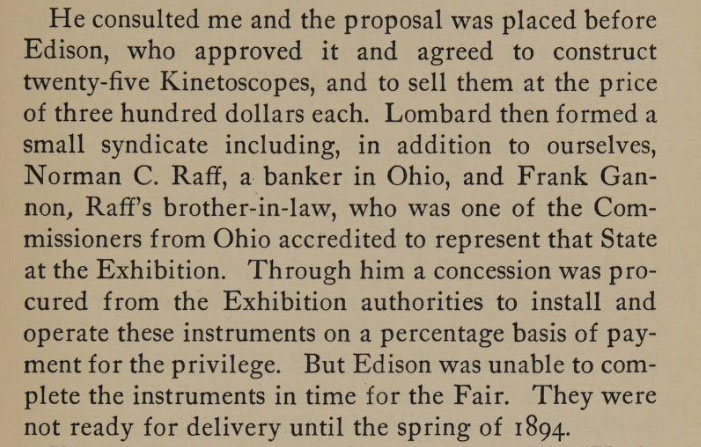

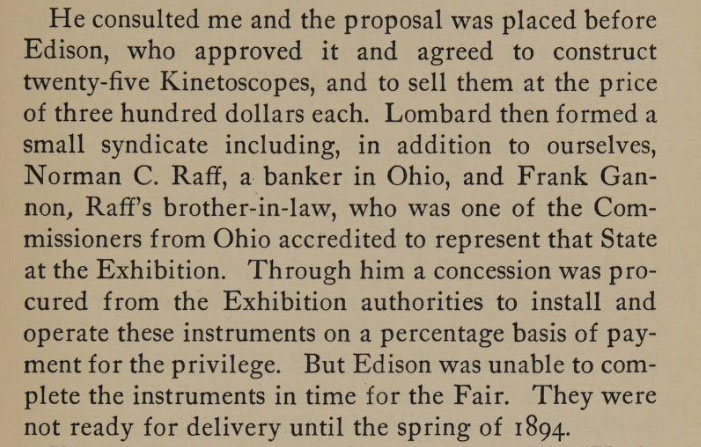

Prior to the opening of the fair there

were negotiations between Edison and Norman C. Raff, Thomas R. Lombard

and Frank R. Gammon which resulted in the rights of sale for the

Kinetoscope and the formation of the Kinetoscope Company. Ramsaye

describes how Raff, Lombard, and Gammon were "eager to introduce

their wonderous machine there. It was the prime opportunity to plant

the seed of a national and world distribution." (5)

Ramsaye then writes that "Edison

had supplies of neither machines nor film pictures for them. He

promised to rush them through. The opening of the Fair in Chicago

was delayed and it seemed possible that a battery of Kinetoscopes

could be ready."

There were efforts by Edison such

as the building of the world's first motion picture studio, the

Black Maria, to try to supply the Kinetoscope Company in Chicago

with films for the kinetoscopes (the "Black Maria" studio

at the Edison Laboratory was completed on February 1, 1893). Raff

and Lombard and the Kinetoscope Company waited for delivery of the

kinetoscopes and their films but Edison's lab had issues with key

personnel who were working on the kinetoscope. Further production

delays ultimately resulted in no kinetoscopes being sent to Chicago

while the fair was still open.

A Million and One

Nights, Ramsaye (5)

Edison did not deliver any Kinetoscopes

to Lombard and the Kinetoscope Company while the fair was open and

Ramsaye is definitive that no

Kinetoscopes were at the World's Columbian Exposition:

Another

explanation of events that contributed to not

even one Kinetoscope making it to Chicago comes

from film historian Charles Musser (7):

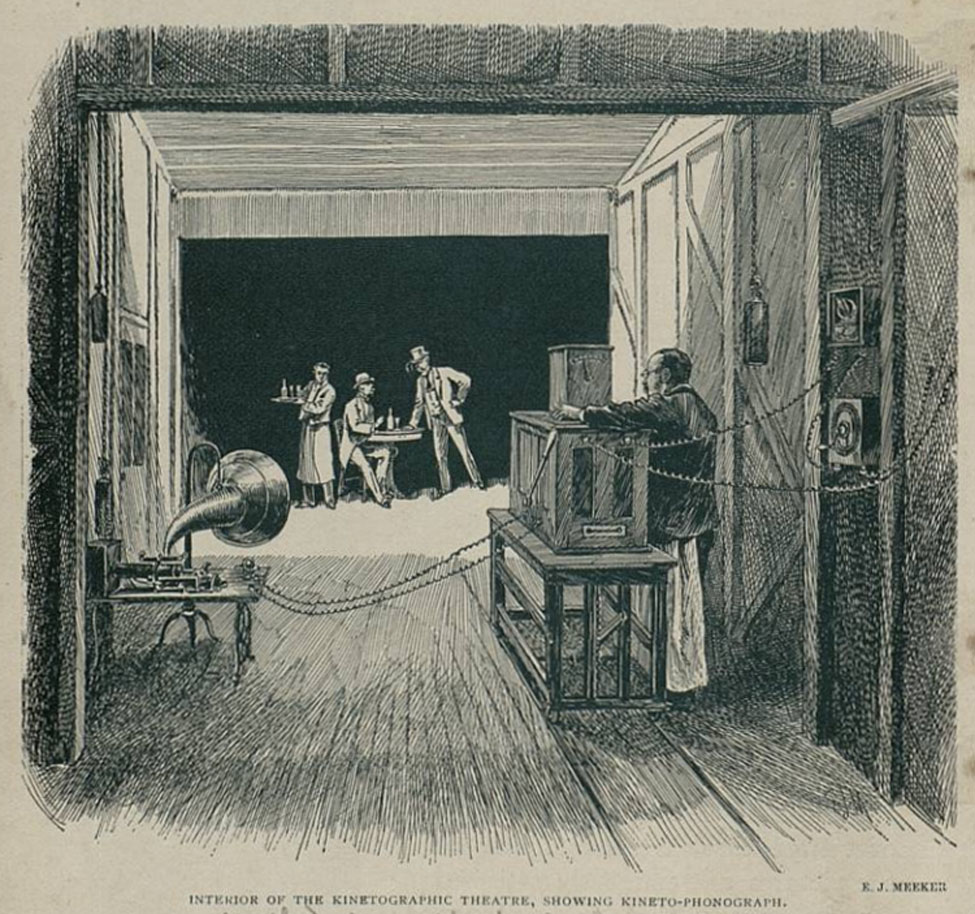

The Black

Maria was rarely used for production during

1893, as the refinement of Edison's motion

picture system and the manufacture of kinetoscopes

experienced delays. W. K. L. Dickson suffered

from nervous exhaustion and was absent from

the laboratory between early February and

late April 1893. Although this accounts for

some of the slowdown, the recession of 1893

may have further impeded this project, as

Edison devoted his hard-pressed finances and

time to iron ore milling. A new model kinetoscope

for films taken with the vertical-feed kinetograph

was probably not available until shortly before

the Brooklyn Institute demonstration in May.

A contract for the manufacture of twenty-five

machines based on this prototype was only

drawn in late June. Gordon Hendricks indicates

that it was given to an Edison employee who

had difficulty staying sober. As a result,

the machines were not completed until March

1894. Only the prototype was available for

exhibition at the Chicago exposition, and

this proved too valuable to send.

If the only kinetoscope

available for exhibition was the prototype that

was displayed at the Brooklyn Institute on May

9, 1893 and it "proved too valuable to

send" then the newspaper articles and pre-fair

publicity were wrong. The public would not get

their chance at the World's Columbian Exposition

of 1893 to see and express anything about the

kinetoscope.

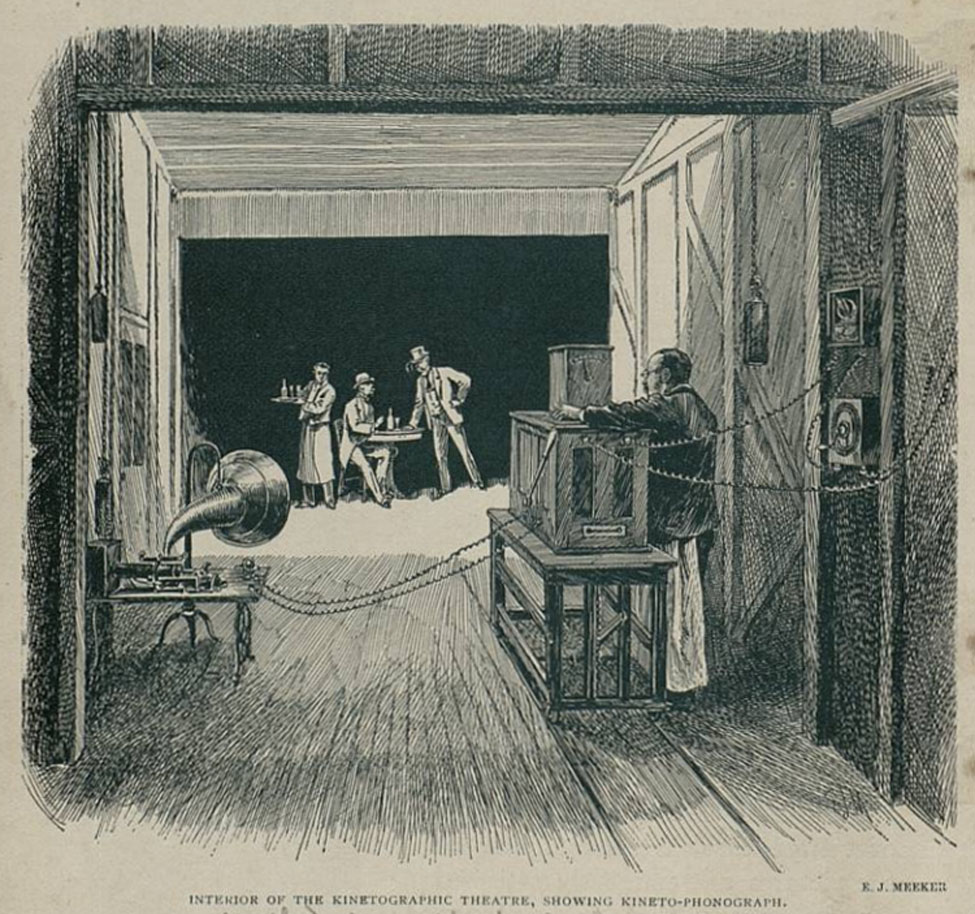

"The Black Maria" at Edison's

Lab which Dickson called "The Kinetographic Theatre" (Courtesy

Library of Congress) (8)

Kineto-Phonograph filming and recording

for moving picture with sound, 1894 (Courtesy Library of Congress)

(8)

The final and most compelling evidence

for answering the question of whether or not any kinetoscope was

at the fair comes from Edison's "Private

Secretary," Alfred O. Tate.

The Phonogram,

March - April, 1893

In his book "Edison's Open Door"

Tate describes his involvement in the original negotiation for kinetoscopes

at the fair and, with his front row seat in Edison's office, makes

it clear that the kinetoscopes were not completed on time and were

never delivered to the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893.

Alfred O. Tate, "Edison's

Open Door," Ibid. 285

Kinetoscope "finally

ready to be seen by the public..."

The experimenting

and development that were required "for the last six or

seven years" before Edison was ready to show his kinetoscope

to the public is mentioned in an April 1894 interview of Edison

and W. K. L. Dickson. Dickson tells the reporter that the kinetoscope

is finally ready to be seen by the public saying "although

their experiments are not yet carried to their conclusion, they

have reached a point where Mr. Edison is willing that the public

should see what they have done." (The

Philadelphia Inquirer, April 1, 1894)

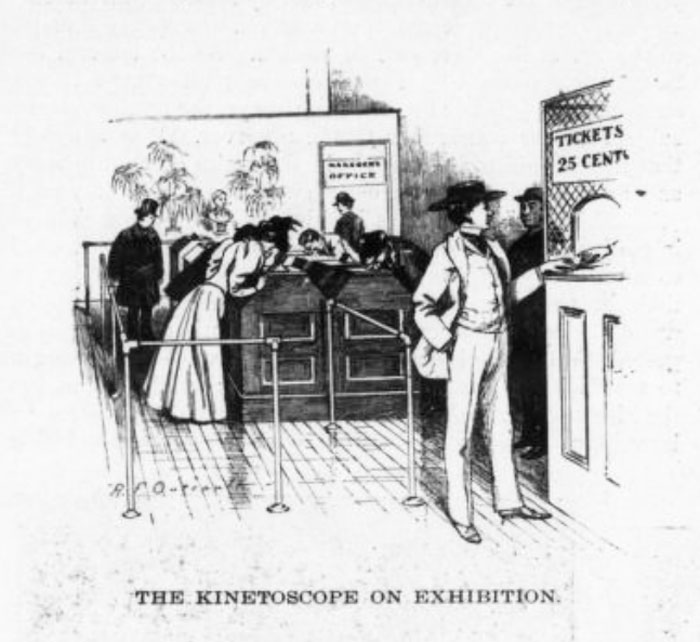

The first kinetoscope shipped by

Edison was part of the delivery of ten machines to the New York

City kinetoscope parlor which went into operation on April 14,

1894 at 1155 Broadway, New York City. (9)

Details

of the Kinetoscope's opening night are described by Alfred

O. Tate in his book "Edison's Open Door."

The Electrical World, June 16,

1894 by Richard F. Outcault (10)

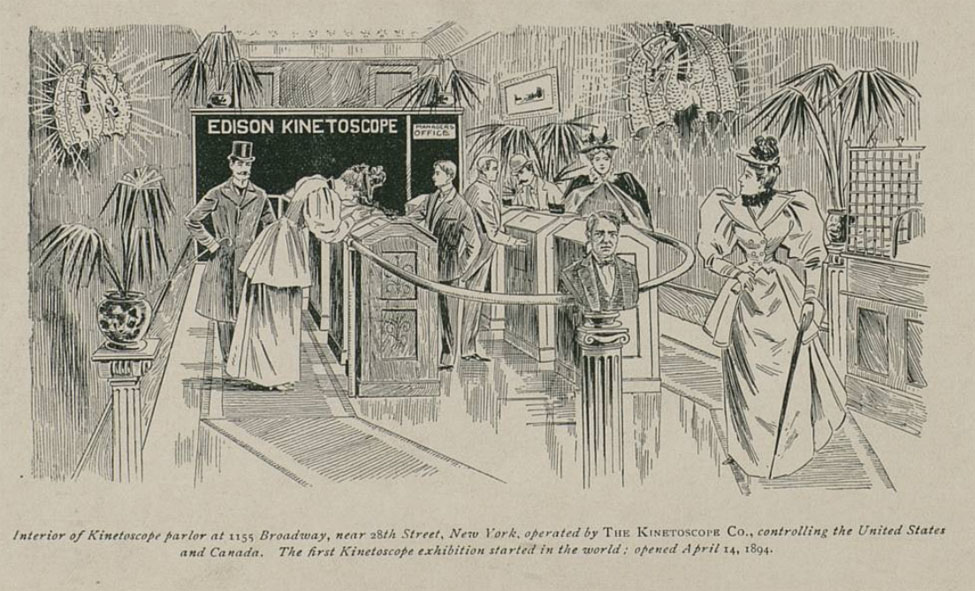

Interior of first Kinetoscope Parlor,

1155 Broadway, New York,1894 (as seen in W.K.L. Dickson's History

of the Kinetograph Kinetoscope and Phono-Kinetograph) (8)

Gordon Hendricks in Origins of

the American Film noted that in this drawing of the parlor

"the Dicksons wanted to give the effect of elegance

in this parlour, and added palms, carpets, and waxed floors --

none of which may have been there: it is difficult to credit the

genteel patronage shown here. Note the incandescent dragons at

right and left and the bronzed bust of Edison in the foreground."

(11)

"The electric dragon with green

eyes" was "an Edison symbol supplied to parlor operators."

(12)

See

FACTOLA about the location of this first kinetoscope parlor.

Conclusion: The

kinetoscope was not at the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893.

There is no evidence that the kinetoscope

was at the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893.

Perhaps there was some type of display

in the southern gallery of the Electricity Building that may have

described what the kinetograph was and what it could do. But even

if a kinetograph exhibit was in that gallery there is no evidence

it was operational and no evidence that any device that "transmits

scenes to the eye as well as sounds to the ear" was at the World's

Columbian Exposition of 1893.

The first kinetoscope

parlor opened in April 1894 in New York City. Parlors in Chicago

and San Francisco quickly followed.

(Courtesy of American

Experience)

The World:Tuesday

Evening, New York, New York, May 29, 1894

Kinetoscope Parlor,

1895 lithograph (magazine)

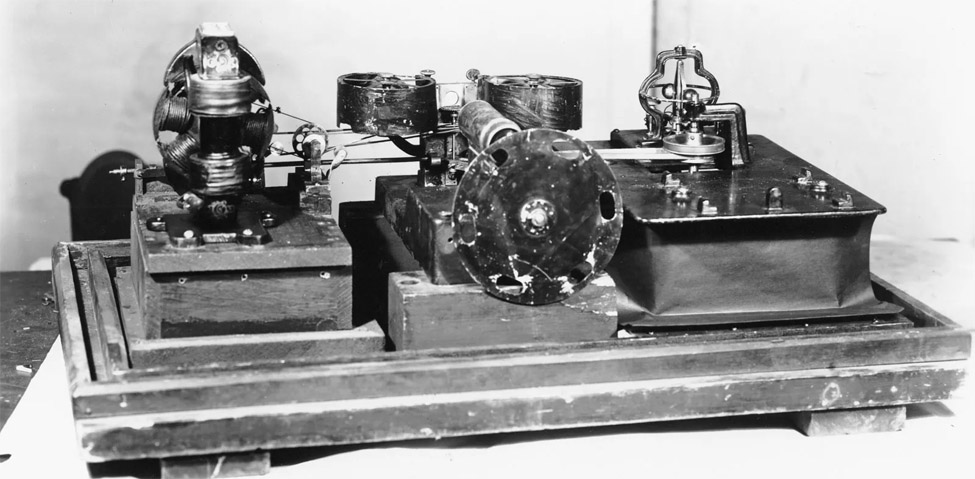

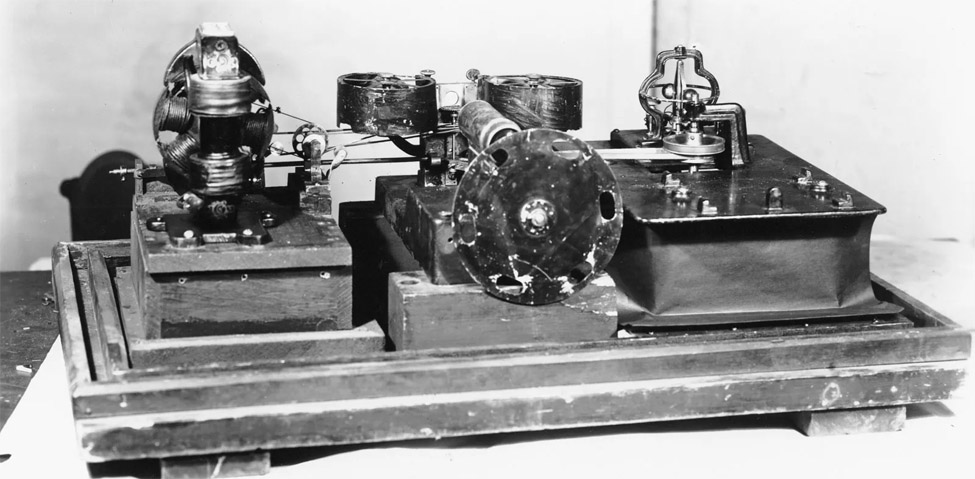

1889 Kinetograph

- The first camera to take motion pictures on a moving strip

of film.

(Courtesy U.S.

Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Edison National

Historic Site)

Reverse side of a

Kinetophone, showing a wax cylinder phonograph driven by a belt

(Courtesy Wikimedia

Commons and Podzo di Borgo).

1 - At the regular monthly meeting

of the Department of Physics of the Brooklyn Institute, May

9, the members were enabled, through the courtesy of Mr. Edison,

to examine the new instrument known as the kinetograph [sic

, i.e., kinetoscope]. - Document

No. 1 - Edison and the Kinetoscope 1888 - 1895, University of

California with original source Scientific

American, May 20,

1893, p. 310 - Musser,

Charles. Before the Nickelodeon: Edwin S. Porter and the Edison

Manufacturing Company. Berkeley: University of California Press,

c1991 1991. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft3q2nb2gw/

2. Robertson, Patrick (2001).

Film Facts. New York: Billboard Books. ISBN 0-8230-7943-0, page

5. (Extracted from Wikipedia "Kinetoscope"

on 2-2-2022)

3. In the September 2, 1893,

issue of Electrical Review, Edison was described

as the Chicago World's Fair alone in the agricultural building

with "a pancake in one hand and a cracker spread with jelly

in the other."

4 - Terry Ramayse, A Million

and One Nights, Simon and Schuster, 1926 (Frontis) Ramayse,

Terry, A Million and One Nights - A History of the Motion Picture,

Simon and Schuster, 1926

5 - ibid "Raff, Lombard,

and Gammon were "eager to introduce their wonderous machine

there..." p. 81

6 - ibid (p.

85)

7 - "The

Black Maria was rarely used for production..."

Musser, Charles. Before the Nickelodeon: Edwin

S. Porter and the Edison Manufacturing Company.

Berkeley: University of California Press, c1991. pp.

38-39

7A - Thomas A. Edison

and his Kinetographic Motion Pictures, Musser,

Charles Rutgers University Press, 1995.

8 - The Kinetographic

Theatre at the Edison Lab - History

of the Kinetograph Kinetoscope and Phono-Kinetograph

by W. K. L. Dickson and Antonia Dickson, p. 53 ©1895

W.K.L. Dickson - University of Minnesota Press’s Library

of Open-Access Titles.

9 - See Edison and

the Kinetoscope: 1888-1895, Chapter

3 Exploitation of the Kinetoscope, p.45 - "Through

Tate, they had a long-standing order for the first

twenty-five kinetoscopes. As soon as these were completed,

ten machines were immediately installed at 1155 Broadway,

near Herald Square in New York City, where the kinetoscope

had its commercial debut on April 14th. A Chicago

kinetoscope parlor, using another ten machines, opened

in mid May..." Source: Musser,

Charles. Before the Nickelodeon: Edwin S. Porter and

the Edison Manufacturing Company. Berkeley: University

of California Press, c1991 1991. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft3q2nb2gw/

10 - Origins of the

American film, Hendricks, Gordon, Arno Press,

New York, 1972 - Hendricks notes that "a possibly

somewhat more realistic view of the 1155 parlor may

be seen in The Electrical World of the June

16, 1894" rather than the April 15, 1894 opening

day interior illustrated in W.K.L. Dickson's History

of the Kinetograph Kinetoscope and Phono-Kinetograph.

11 - Hendricks Ibid.

Drawing number 36 - Comments from Hendricks about

Dicksons' History illustration of "Interior

of Kinetoscope parlor" which "opened April

14, 1894."

12 - Hendricks Ibid.

p. 59 - "the Edison symbol of an electric dragon

with green eyes, supplied to parlor operators, is

plain in the drawing of the 1155 parlor and elsewhere

in the literature."

13 - Robinson, David,

"From Peepshow to Palace The Birth of American

Film," Columbia University Press, New York,

1996. "Magic Lantern" vs. "Stereoptican"

nomenclature footnote, pp 3 - 4.

The

Kinetoscope - An American Experience PBS video

In the

1890s, Thomas Edison worked with his assistant and

part-time photographer, William Dickson to create

a motion picture camera. They created a series of

short films that could be viewed on a coin-operated,

peephole viewing cabinet called a kinetoscope. (3

minutes 32 seconds from 2015 PBS American Experience).

Wilkes-Barre

Times Leader The Evening News, May 28, 1891

- IT OUTEDISONS EDISON. The Latest Wonder from the

Wizard's Workshop.

Chicago

Tribune, May 13, 1891- Edison and the Big

Fair - "The Kinetograph and What He Claims for

It"

Chicago

Tribune, May 28, 1891 - "Light and Sound

United - Edison Outdoes Himself with the Kinetograph"

The

Pall Mall Gazette, London, May 29, 1891 - Mr. Edison's

Latest Invention. The Wonders of the Kinetograph.

Chicago

Tribune, October 7, 1891 - Wonders of the Kinetograph.

The

Phonogram, October 1892, The Kinetograph - A New Industry

Heralded

The

Historical World's Columbian Exposition and Chicago Guide,

Pacific Publishing Co., 1892

Ottawa

Daily Citizen, March 10, 1893 - Makes a Shadow Talk.

150 of Edison's Odd Inventions at the World's Fair

The

Chicago Tribune, March 23, 1893 - Concessions granted

for 50 Tachyscopes on Midway Plaisance

The

Indianapolis News,

April 27, 1893 p. 5

The

Champion, Norton, Kansas, April 27, 1893 -

Edison's World's Fair

Exhibit

The

Madison Chronicle, Madison, Nebraska April 27, 1893

- Edison's Latest Wonder. He Will Exhibit a Mechanical Retina

Which He Calls a Kinetograph.

The

Lindsborg's News Lindsborg, Kansas April 28, 1893 - Edison's

World's Fair Exhibit.

The

Standard Union, Brooklyn, May 10, 1893 - "Wizard

Edison - A Wonderful Instrument of His Exhibited at Brooklyn"

Scientific

American, May 20, 1893 - First Public Exhibition of Edison's

Kinetograph,

The

Evening World,

New York, May 28, 1891 - EXTRA "Edison's Newest

Wonder - The Kinetograph, A Surprising Invention for Reproducing

Motion"

The

Tennessean, Nashville, June 20, 1891 - "The

Kinetograph. Edison's Latest Invention - A Companion to the

Phonograph"

Vermont

Watchman and State Journal, Montpelier, VT, July 1,

1891 - "The Kinetograph."

Notes

from the Exposition by

J. C. Ruppenthal, Jr., The Russell Record, KS, July

13, 1893 - Edison Phonograph and Graphophone Coin-Ops and

Tachyscope

Aurora

News-Register, Aurora, NE July 18, 1891 - "Edison's

Kinetograph. It Will Be Far More Wonderful Than the Phonograph."

The

Alton Weekly Telegraph,

July 13, 1893 "The Kinetograph and Kinetoscope"

- "almost ready to be put upon the market but still at

Edison's Lab."

The

Brooklyn Daily Eagle,

July 16, 1893 - "SEE

THE FAIR FOR $100 - Story of a Brooklynite Who Took His Wife

to Chicago"

The

Waco News, The

Waco Evening News, August 19, 1893 - From Nan Manlove

Toby's column "IN SOCIETY - An Interesting Letter

From the White City."

St.

Louis Globe-Democrat, December 10, 1893- Edison's

Latest Inventions.

The

Pensacola News, August 23, 1893 - "Edison's Latest

- The Phono-Kinetograph Will Soon Be Brought Out"

Person

County Courier, Roxboro, NC, November 23, 1893 - Terms

Kinetoscope and Kinetograph

American

Society of Cinematographers - Overview of the Kinetoscope

and their restored Kinetoscope.

Muybridge's

Zoopraxographical Hall at the World's Columbian Exhibition

The

World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. Trumbull

White and Wm. Igleheart, published by J. S. Ziegler &

Co., Chicago, IL, 1893. Edison's Exhibits and Kinetograph,

p. 326.

Edison

Barber Shop Film, December 1893

The

Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia, PA, April 1,

1894 - "The Wonderful Kinetoscope - Edison's Latest Invention

Reproduces Nature's Movements with Wonderful Fidelity"

The

Inter Ocean by George M. Smith, Chicago, IL, April

8, 1894 p. 33 - "The Kinetoscope - A Sequel to the Kinetograph

Invention" (See Philadelphia Inquirer for April

1 report)

The

Larned Eagle-Optic,

April 20, 1894 - Wizard Edison's Latest - The Wonderful

Kinetoscopes and the Marvels It Accomplishes (Example of how

large and small newspapers repeated this story)

Edison's

personal testimonial to Ramsaye's research and "unrelenting

effort at exact fact."

Fairground

Fiction in Newspapers - Letters to the editor and visitor

accounts about the 1893 World's Fairs and printed in newspapers.

|