Why

December 6?

The

Birthday of the Phonograph is December 6, 1877

Why

December 6th?

Friends

of the Phonograph

celebrate the Phonograph's birthday

on December 6 to mark the completion of Edison's Phonograph

and the decision by Edison that his invention was ready to be

heard by the public.

FACTOLA:

On December

4, 1877, Charles Batchelor, one of Edison's aids, recorded in

his diary "Kruesi made the phonograph today." Edison

Cylinder Records 1889 - 1912 With an Illustrated History

of the Phonograph, Allen Koenigsberg, APM Press ©1987.

p. xii.

FACTOLA:

On

December 6, 1877, Charles Batchelor

"recorded in his diary "Kruesi finished the phonograph." Ibid.

FACTOLA: On December 7,

1877 Edison's infant invention was taken to the office of Scientific

American where the Phonograph introduced itself. (See Note:

2 for more details about this date). This public

debut of the machine which Edison would later call his "favorite

invention" and his "baby"(2A),

was subsequently described in the December 22, 1877 issue of

Scientific American. The Papers of Thomas A. Edison, Vol.

3, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, ©1994,

p. 659.

FACTOLA: On December 7,

1877 The Kruesi patent model (wood) was completed. The work

sheet for it survives and is illustrated in "Edison Cylinder

Records 1889 - 1912," Allen Koenigsberg, 2nd edition 1987.

The original patent model is in the Collections of The Henry

Ford at Dearborn, Michigan. See Kruesi

patent model Endnote for details.

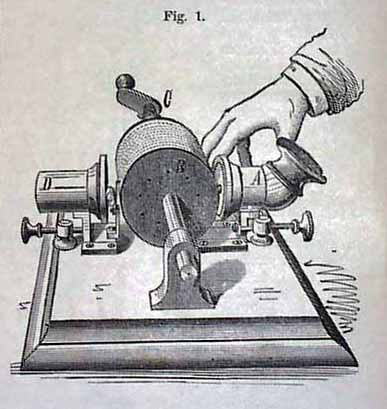

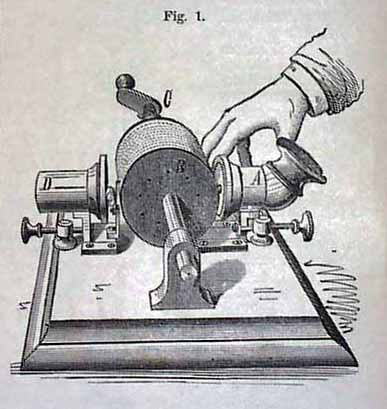

Patent Model for

Edison's 1877 Tinfoil Phonograph (From the Collections

of The Henry Ford. Gift of the Edison Pioneers.)

The

Phonograph's Birthday Timeline

Edison's phonograph timeline includes

dates leading up to its 'birth'.

The following are dates related

to the capture and study of sound waves, conception of recording

and reproducing sound, telephone related experiments, the Edison

phonograph's construction, testing and word(s) 'first' spoken

and repeated back, patent filing, and phonograph demonstrations.

For an overview of the history of

recorded sound see "The

Birth of the Recording Industry" by Allen Koenigsberg

©1990.

March 25, 1857 - Édouard-Léon

Scott patented his Phonautograph. The phonautograph is the earliest

known device for recording sound. At the time it was not the intention

of Scott to reproduce sound but rather to study what sound waves

looked like and potentially transcribe.

April 9, 1860 - The

first line of "Au clair de la lune" was recorded by

Édouard-Léon Scott on his Phonautograph. These recorded words

were at one point called "the earliest

clearly recognizable record of the human voice yet recovered"

(although these words were not actually heard until 2008 with

the help of computer technology). Since then "even older

recordings" have been "identified and played back."

See FirstSounds.org

for the most current information and access to "humanity's

earliest sound recordings."

April 30, 1877 - Charles

Cros submits a sealed envelope containing a letter to the Academy

of Sciences in Paris explaining his proposed method for recording

and reproducing sound. Although this envelope was not opened until

December 3, 1877, Cros should, at minimum, be credited "with

anticipating, though barely, what Edison was to accomplish"

(12) and describing an

invention which he named the Paleophone (voix du passé).

July 17, 1877 - The Speaking

Telegraph - Edison Lab Notes (3) reads: "Glorious = Telephone

perfected this morning 5 am = articulation perfect -- got 1/4

column newspaper every word. -- had ricketty transmitter at that

-- we are making it solid." (Note: The Philadelphia Inquirer

for Tuesday, July 17,1877, ran an article describing the rehearsal

at the Permanent Exhibition).

Phonograph historian Patrick Feaster

notes that on this date "Edison and his associates sketched

out the principle of phonographic sound" (4).

July 18, 1877 - Edison "announces"

his intention to invent the phonograph.

(5)

The Thomas A. Edison Papers Project

describes the July conception of the future Phonograph as follows

(6):

In July 1877, while

developing his telephone transmitter, Edison conceived the idea

of recording and playing back telephone messages. After experimenting

with a telephone "diaphragm having an embossing point & held against

paraffin paper moving rapidly," he found that the sound "vibrations

are indented nicely" and concluded "there's no doubt that I shall

be able to store up & reproduce automatically at any future time

the human voice perfectly." Edison periodically returned to this

idea, and by the end of November, he had developed a basic design.

End of July 1877

- Edison "constructed a paraffin paper device called a telephonic

repeater" which in the "course of many experiments thought

he could hear the sound of human voices or music when the strip

of paper moved quickly beneath the spring-driven point. Inspired,

he quickly yelled "Halloo" into the crude mouthpiece,

and was completely taken aback when the machine faintly imitated

him moments later. (7)

July 30, 1877 -

Edison filed a patent application in great Britain, No. 2,909, and

"disclosed not only a cylinder phonograph, but also an apparatus

embodying his original conception of an embossed strip." Thomas

Alva Edison - Sixty Years of an Inventor's Life by Francis Arthur

Jones, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1907, p 244.

August 12, 1877

- The Library of Congress' website America's

Story assigns this as the "date popularly given for

Thomas Edison's completion of the model for the first phonograph.

(8). See reference 7 (above). See cover

below postmarked Edison, NJ August 12, 1977 (but not First Day

of Issue postmark).

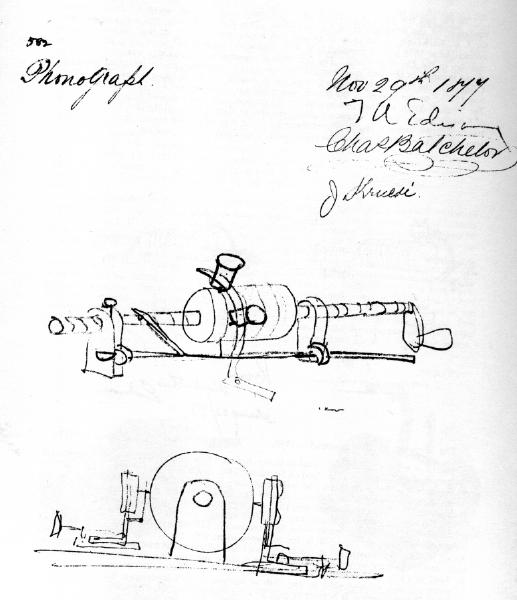

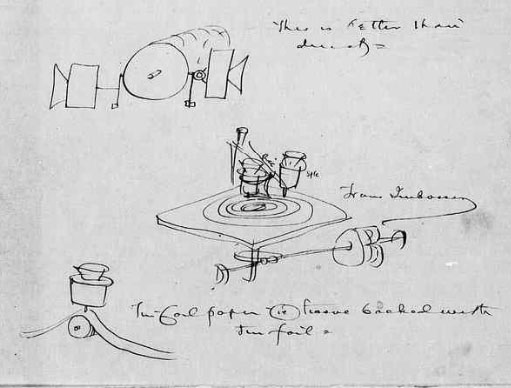

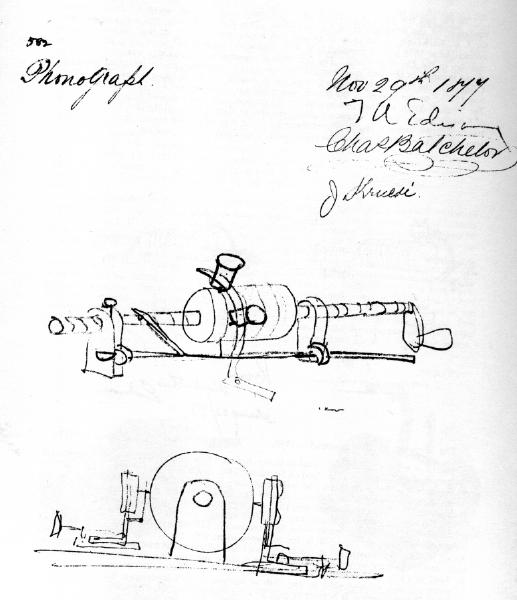

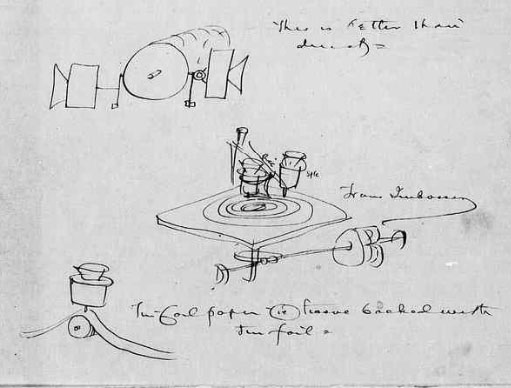

November 29, 1877

- Basic sketch of the Phonograph completed that apparently was the

"sketch that his workman, John Kruesi, used to construct the

first tin-foil model." (9)

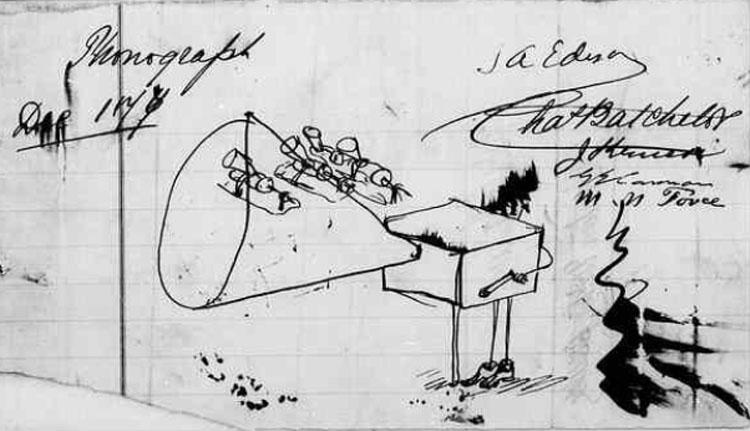

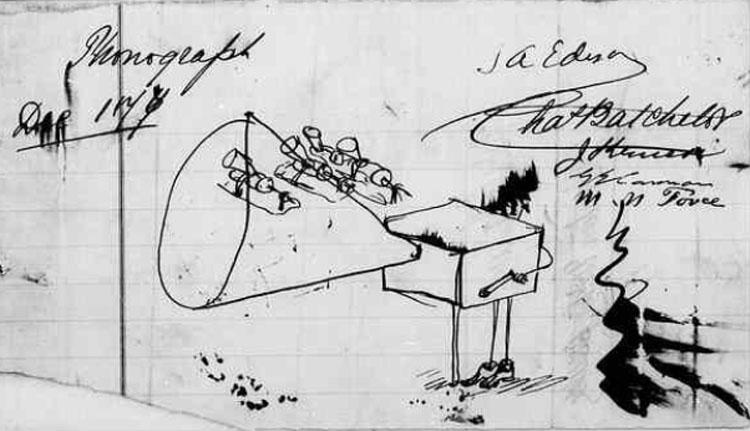

First sketch of the Phonograph -

November 29, 1877 (Edison Cylinder Records, 1889 - 1912 With

an Illustrated History of the Phonograph, Allen Koenigsberg,1987,

p. xiv).

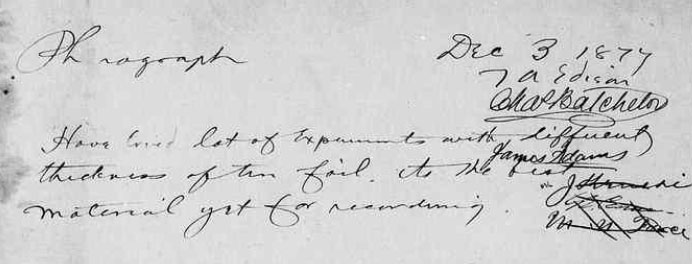

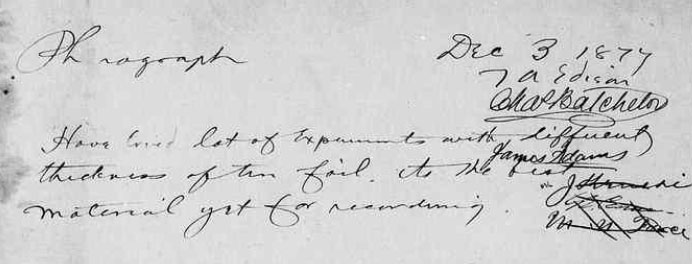

December 3, 1877 - Experimenting

with different thickness of tin foil. Batchelor writes in the Technical

Note (signed by Chas. Batchelor, T. A. Edison and James Adams) titled

Phonograph Dec 3, 1877 "Have tried lot of experiments with

different thickness of tin foil. Its the best material yet for recording."

That conclusion by Batchelor indicates that sound is being recorded

and played back.

Provided by The

Thomas A. Edison Papers at Rutgers University [NV17021]

Editor's Notes for December

3 also included the "Organ grinder phonograph; illustration for

11/23 proposal for uses of phono."

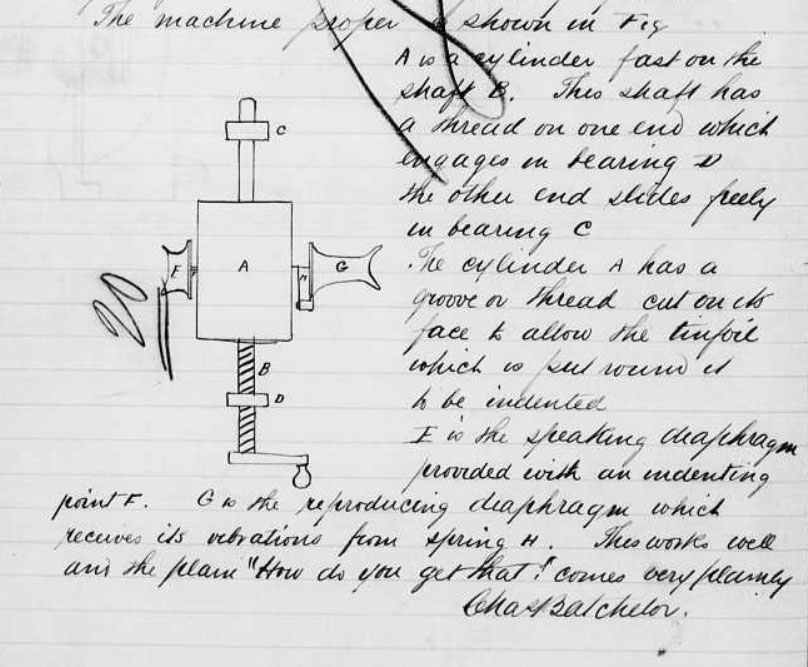

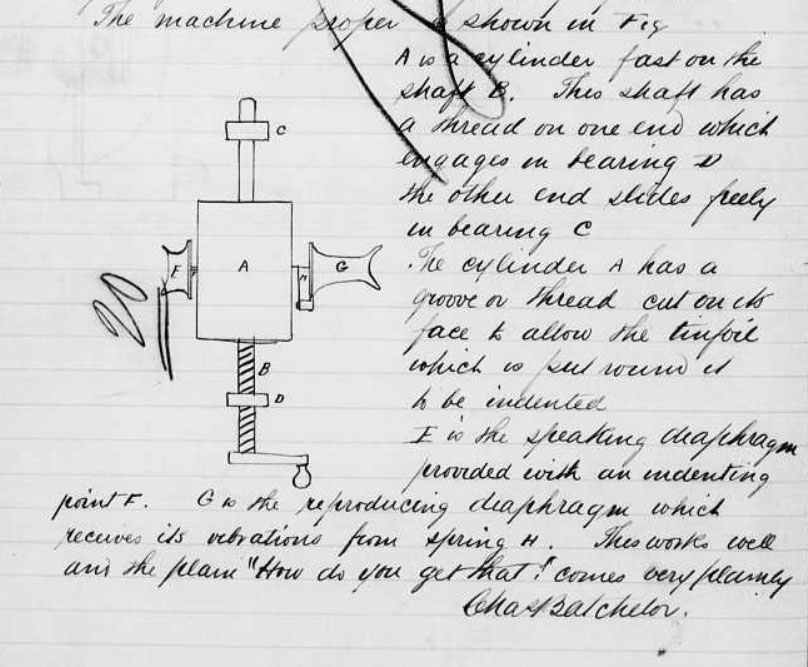

December 4, 1877 - "Kruesi

made phonograph today." (10)

Testing is being done using the phonograph

that Kruesi has made on December 4 and it's documented that the

phrase "How do you get that" was recorded and repeated

back before Edison's December 6th reciting of "Mary had a Little

Lamb." The following Technical Note includes Batchelor commenting

that sound is being reproduced very well by the reproducing diaphragm

and includes a figure of the phonograph. Batchelor writes: "G

is the reproducing diaphragm which receives its vibrations from

spring H. This works well and the phrase "How do you get that"

comes very plainly. Chas. Batchelor."

Provided by The Thomas

A. Edison Papers at Rutgers University [NV17021].

December 6, 1877 - "Kruesi

finished the phonograph." (1)

Kruesi finishing the phonograph meant

it was built and ready to be tested by Edison.

The Thomas A. Edison Papers Project

(11) describes the events

of December 6 as follows:

"When Kruesi finished making

the phonograph Edison put on the tin foil and then recorded the

nursery rhyme "Mary Had a Little Lamb"; Edison's daughter Marion

was at the time nearly five years old and his eldest son was almost

two. Edison then "adjusted the reproducer and the machine reproduced

it perfectly. I never was so taken back in my life. Everybody

was astonished. I was always afraid of things that worked the

first time."

The "How do you get that"

of December 4,1877 and other words that were spoken, recorded and

repeated back during the experimenting, building and testing of

the Kruesi tinfoil phonograph (prior to Edison's December 6 "Mary

had a Little Lamb") are certainly part of the phonograph's

development.

For Friends of the Phonograph,

however, words that were heard before December 6, 1877 are interpreted

as having taken place before Kruesi turned over his "finished"

work to Edison and while the Stork was still in route for the delivery

of Edison's "baby."(2)

Addressing December 6th as the phonograph's

birthday, Allen Koenigsberg, long-time phonograph collector and

publisher of The Antique Phonograph Monthly (1973-1993) liked

the December 6 birthday date but added some "twists."

In Allen's words "Certainly Dec 6th is better than the various

others that have floated during the last century. There are always

slight twists to these things, as didn't Batchelor give Dec 4, for

"How do you get that" as the first recorded words? (before "Mary").

On the other hand, there is (also) the 'Halloo Phonograph' (pre-cylinder)

of late July 1877, which looked like a flat slide-rule, and held

a small strip of paraffined paper (enough for one word anyway).

TAE refers to it in early Feb 1878." (1A)

In short, all three conditions are

met for the Phonograph's Birthday being on December 6 with its delivery

and birth completed on December 6: 1) Kruesi finished the

Phonograph on December 6; 2) Edison spoke and then heard what he

later said were his "first words into the original phonograph,

a little piece of practical poetry: Mary had a Little Lamb"

on December 6; and 3) Edison made the decision on December 6 that

his Phonograph was finished and ready to talk to the world which

he would do the next day by taking the phonograph to the office

of Scientific American where the precocious phonograph would

introduce itself.

December 7, 1877 - Phonograph

taken to offices of Scientific American by Thomas A. Edison,

Charles Batchelor, and Edward Johnson for its first public

demonstration.

On December 7 and with the Phonograph

1 day old, the Phonograph visited the office of Scientific American

in New York City where it would introduce itself and make remarks

that "were not only perfectly audible to ourselves, but to

a dozen or more persons gathered around."

The phonograph's demonstration resulted

in Scientific American's article "The

Talking Phonograph" which reported that Edison's "little

machine" was able to record the vibrations of the human voice

and, when played back, repeated what was "nothing else than

the human voice." Believing

that the Phonograph could have an "astonishing" future

they were also recognizing that the human perception of ephemeral

sound would never be the same when they wrote it "is impossible

to listen to the mechanical speech without his experiencing the

idea that his senses are deceiving him."

December 15, 1877 - Edison's

application for Phonograph patent executed.

December 22, 1877 - Scientific

American publishes story about Edison's Phonograph.

December 24, 1877 - Edison

patent for Phonograph filed.

February 19, 1878 - U.S. Patent

No. 200,521 granted for Edison's Phonograph.

April 18, 1878 - Edison in

Washington D.C. to demonstrate his Phonograph to the National Academy

of Sciences.

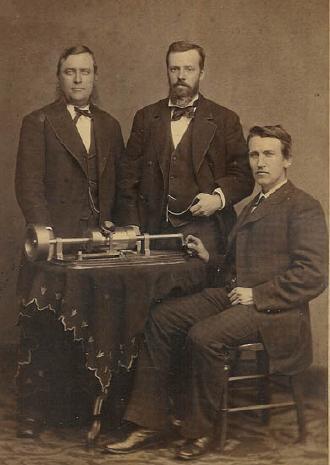

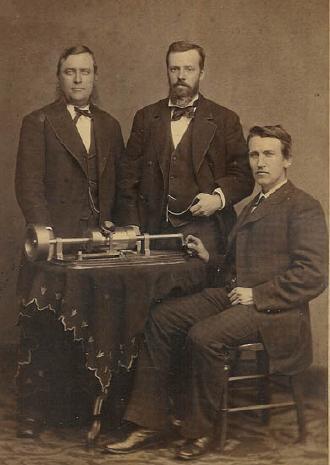

Thomas Edison seated with his "Brady"

tinfoil Phonograph, April 19, 1878 in the studio of Mathew Brady.

Standing left to right are

Uriah Painter and Charles Batchelor. Courtesy of the Edison National

Historic Site.

For examples of postage stamps issued

for the Centennial of Sound Recording and respective First

Day of Issue Covers (FDC), see Phonographia's Phonograph

First Day Covers and Stamps.

Special

thanks to Allen Koenigsberg, The Thomas Edison National Historical

Park, Rutgers School of Arts

and Sciences "Thomas A. Edison Papers,"

and the Henry Ford "Museum of American Innovation."

The 1898 Revisionist History by

the Columbia Phonograph Company for the Birth and Life of the Talking

Machine.

For the Revisionist History of the

invention of the first talking machine presented by Mr. J.

J. Fisher in 1898 see the following article from The

Phonoscope, December 1898.

J. J. Fisher recorded songs for the

Columbia Phonograph in 1898 and it was Fisher's recorded message

which was used as the opening address at the Waldorf-Astoria "to

present the case that the Columbia Phonograph Company's patented

"discovery that sounds could be recorded by a process of

engraving on a wax-like material" was what provided "the

life of the talking-machine art, which has no existence before it

was made and could not exist without it. In 1888, Mr. Edison borrowed

the discovery of Bell and Taintor and used it in an instrument to

which he gave the name borne by his absortive (sic ~ abortive?)

attempt of 1877....The credit for the original discovery belongs

to Bell and Taintor."

To emphasize the claim that Edison's

original "old tin-foil Phonograph was a mere toy of no practical

value and was very soon dropped by himself" (Edison) and

that "the life of the talking-machine art" belonged

to the lineage of the Columbia Phonograph Company, a Columbia Graphophone

Grand was used to provide the following recorded "address"

by Mr. J. J. Fisher. It was reported that "every word of Fisher's

recorded message was "clear, distinct and natural in tone."

Note: This article begins by describing

the context as "an exhibition of the Graphophone Grand"

so it was clearly a Columbia Phonograph Company sponsored event.

At the end of Fisher's recorded address it is further confirmed

by Fisher simply adding "that anyone desiring further information

on this fascinating subject can obtain it at either of the offices

of the Columbia Phonograph Company, whose numbers are on the pragram

(sic)."

It's also noteworthy when reading

this address to remember the on-going litigation that was

part of the phonograph's post-1888 history, particularly involving

Edison, Columbia and the Victor (Berliner) Companies.

The

Phonoscope, December 1898.

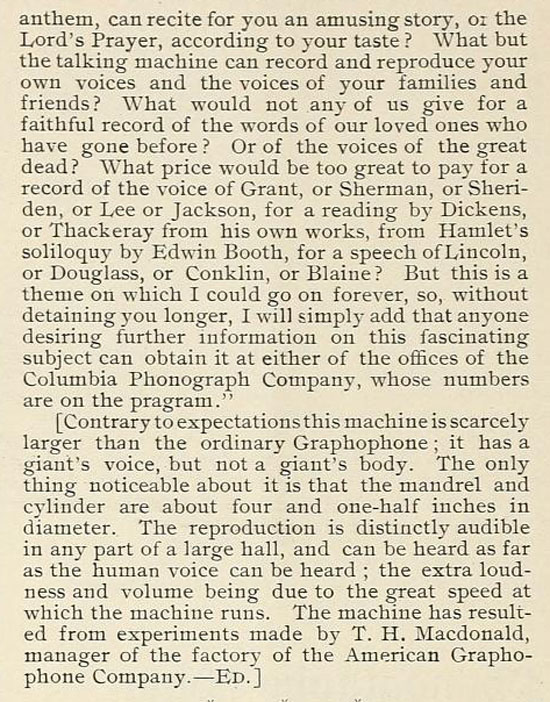

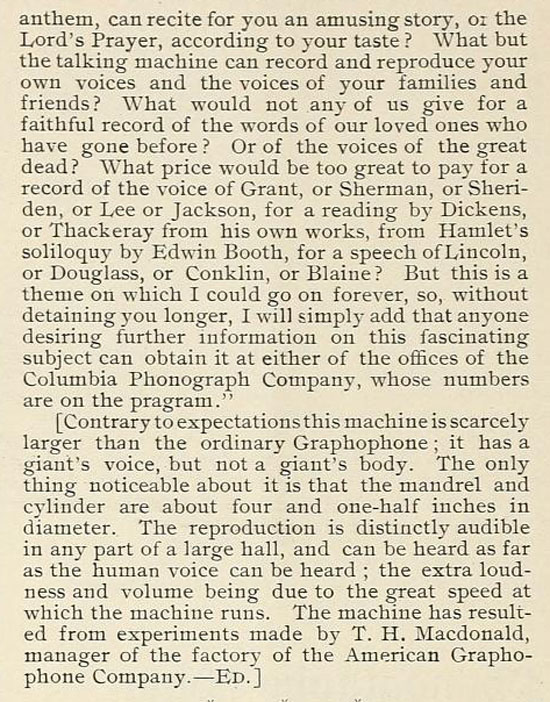

"The Graphophone

Grand - The Greatest Improvement in Talking Machines in the

20 Years,"

The Phonoscope, December 1898.

Note: J. J. Fisher recorded for the

Columbia Phonograph Company and made the following record for Columbia

circa 1898.

LISTEN:

Savior pilot me. [Jesus,

savior, pilot me] - by. J. J. Fisher, Brown wax cylinder. Columbia

Phonograph Co.: 9123. Released between 1898 and 1900. (Source: UCSB

Cylinder Audio Archive, John Levin Collection.) Released between

1898 and 1900.

Fisher also recorded for Berliner,

Edison, Zonophone, Victor, Climax, Oxford, et al.

T. W. Searing

Another claim regarding

the First Engraving of Recorded Sound headlined "Claims

to be the First Inventor of the Talking Machine" was published

in a letter to The Phonoscope, published December 1898 from

T. W. Searing. As was the case in J. J. Fisher's "address"

made on behalf of the Columbia Phonograph Company, neither Bell

& Tainter or Searing are able to state that they invented the

first device which could record and playback those recorded

sounds. The engraving vs. indentation method of recording would

be heavily litigated and cross-patents would be implemented. But

it misses the point and should not be given parental rights for

the birth of the phonograph.

Additionally, if it

was simply the issue of recording sound waves of the human voice

on a medium that could later reproduce that voice then the role

of Édouard-Léon

Scott de Martinville also needs to be included.

For Friends of

the Phonograph, however, it is a FACTOLA that

all three conditions were met by Edison on December 6, 1877 to establish

the patrimony, delivery and birth of the first talking machine.

1) Kruesi finished the Phonograph

on December 6;

2) Edison spoke and then heard what

he later said were his "first words into the original phonograph,

a little piece of practical poetry: Mary had a Little Lamb"

on December 6;

3) Edison made the decision on December

6 that his Phonograph was finished and ready to talk to the world

which he would do the next day by taking the phonograph to the office

of Scientific American where the precocious phonograph would

introduce itself.

Happy Birthday to Edison's Phonograph

- December 6, 1877.

The

Phonoscope, December 1898.

Last Updated: December

6, 2023

Phonographia

|