Collecting

and Phonographia

One

Collector's Perspective

By

Doug Boilesen 2018

My

phonographia

collection began when I purchased a Victrola at age twelve with

money from my paper route. Auctions and antique stores were early

sources for adding to the collection but I didn't pursue many

machines and certainly not rare ones.

Through

the years my collecting interests took some turns but collecting

always revolved around phonographs and its related ephemera.

Why

this fascination with talking machines, recorded sound and phonograph

ephemera?

Here

are three possibilities.

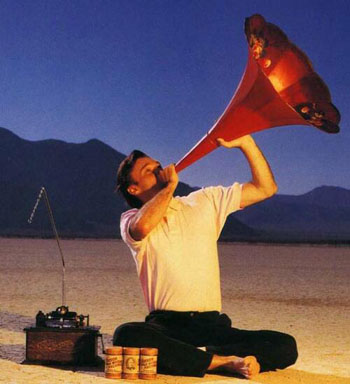

First,

the phonograph is based on a very simple technology yet what it

did was revolutionary and almost magical. It was revolutionary

because it changed human's perception of sound. It was a wonder

and magical because it was initially an early example of Arthur

C. Clark's adage known as his Third Law, i.e., "Any

sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic."

As the phonograph moved into the home, however, it became part

of everyday life and lost its magic.

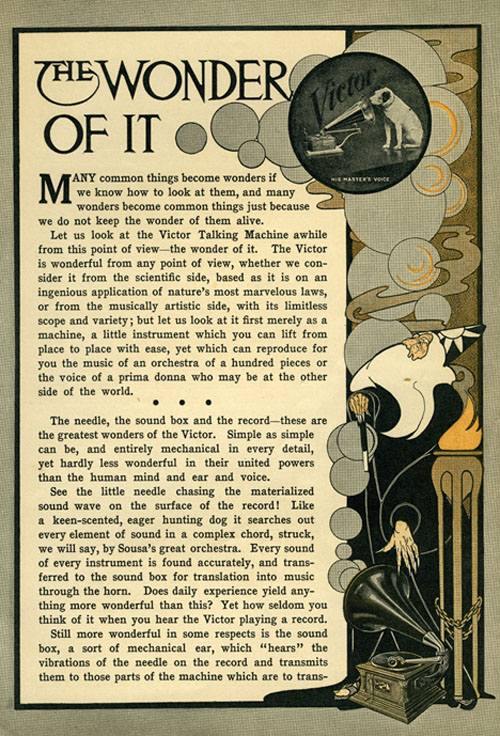

Victor Advertising

Brochure 1906 - "Does daily experience yield anything

more wonderful than this?"

Second,

the phonograph is an interesting example of how one invention

can produce so many popular culture ripples and connections --

and not just for one generation. In fact, the phonograph has played

in every decade since its invention and still plays music from

its grooves today by the vinyl enthusiasts of the 21st century.

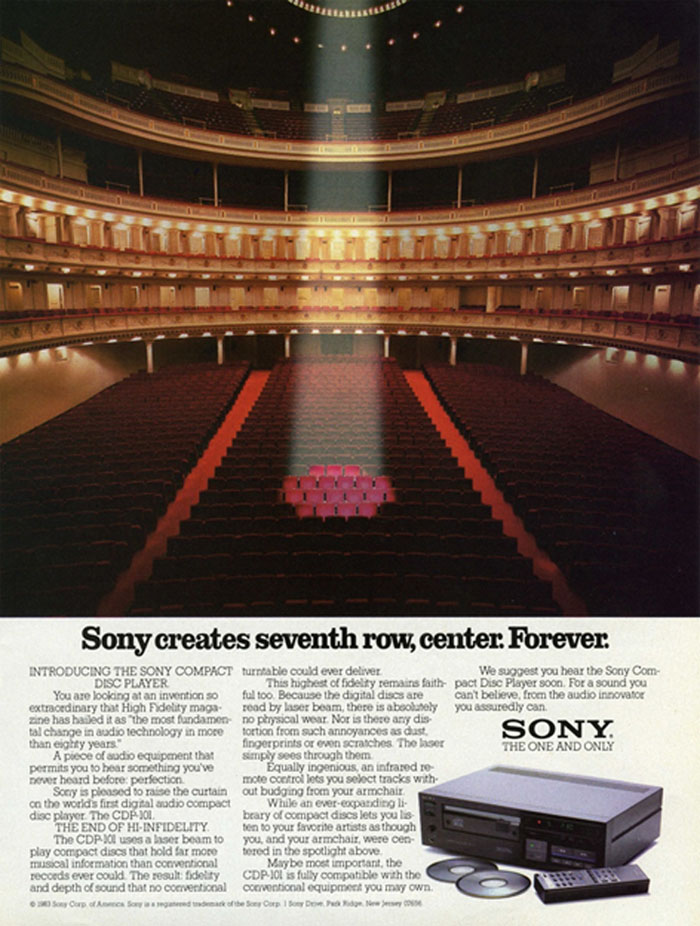

The phonograph's advertising themes likewise have been repeated

each decade up to the present. Descendent home entertainment devices

continued the phonograph's advertised promise of offering personal

entertainment to anyone, anytime and as often as you wanted.

And

third, early phonographs such as morning-glory horn machines and

stately Victrolas are icons of recorded sound and home entertainment

with its story told by museums, social and cultural historians,

and collectors. (5A)

As

part of consumerism promoting the home is your castle the

phonograph uniquely offered everyone in the family the "best

seat in the house." That theme has been in home entertainment

ads since the mid-1890's and has never stopped.

Every

new home entertainment device using recorded sound has promoted

that "best seat" message: the phonograph with its multiple

record speeds and hundreds of millions of records; the radio;

the television; the tape recorder; VCRs, CDs, Laserdiscs and CED

Video Discs, DVDs, audio books, music streaming services, etc.

-- each of these sound and entertainment providers continued

the phonograph's revolutionary promise that your home could be

your own "Stage of the World" -- entertainment experiences

of the world were available to you as if you were a king, or a

millionaire or the possessor of Aladdin's Lamp.

"Seventh

row, center. Forever."

And

what about collecting?

Lorenz

Tomerius wrote that some objects become different or more interesting

based on use and ownership:

"This

refutes Gertrude Stein's claim 'a rose is a rose is a rose': that

it has become a different object if Napoleon wore it on his uniform.

A key is no longer a key if it belonged to the Bastille. A knitting

needle is an object with a special aura if Marie Antoinette made

it rattle, and a shaving kit will evoke horrible associations

if it was once owned by Danton." Lorenze Tomerius, 'Das

Glück, zu finden, Die Lust, zu zeigen' (2)

Finding Marie Antoinette's

knitting needle in the haystack would exemplify one aspect of

collecting. But there is also the more general practice of collecting

where the goal is to have all or subsets of the whatever, such

as stamps, coins, beanie babies, baseball cards, etc.

My collecting has never

been about owning all the models of phonographs made by Edison

or acquiring objects with a special provenance related to ownership

or use. Caruso didn't previously own the Victrola in my collection

and I don't own Andy Kaufman's record player with its Mighty Mouse

record that he used in the premier episode of NBC Saturday

Night Live, October 11, 1975. (3)

Andy Kaufman's phonograph

playing the Mighty Mouse theme song. (Courtesy NBC and

Saturday Night Live, 1975).

Instead, each object

is a "rose is a rose is a rose" in my collection of

phonographia.

But how many roses

does a collector need and what is to be done with them after they

are acquired?

Regardless of that

number the constant for me has consistently been the relationship

each 'rose' has to popular culture. Phonograph connected advertisements,

postcards, greeting cards, Valentine's cards, jokes, cartoons,

art and record album cover art each show how the phonograph's

revolution was seen in popular culture and daily life.

My collecting of objects

and ephemera has been like cutting out newspaper clippings or

saving ephemera to go into a personal scrapbook. Each selection

has its own identity and its own meaning. Ownership of phonographia

is not required to find and follow phonograph connections but

collecting has been the catalyst to see the connections and create

phonographia.com as an on-line scrapbook.

Caruso standing next

to his Victrola Queen Anne XIV

I believe phonographia

bridge time allowing us to glimpse and hear fragments of other

eras because relevant objects and stories and sounds have been

collected.

Researchers tell us

that recognition, one of the two primary forms of accessing memory

"is a simpler and more reliable process" than recall.

"It is the association of a physical object with something

previously encountered or experienced. This could be because tangible

memories utilize all five senses, evoking emotional triggers and

transporting us back to a precise time, place or moment."

(3A)

Although historical phonographs cannot be encountered by us in

their own time period, collected objects and stories and sounds

related to the phonograph can still transport us to a time that

we personally didn't experience.

In a 1995 Syracuse

University address about the Belfer Audio Archive, John Harvith

said that the Belfer Archive was important because it

"allows us to feel this sense of history even more vividly,

because we can hear what musicians, artists, authors, actors,

statesmen, politicians, and other historical figures actually

sounded like. This is emotional, visceral communication that goes

far beyond the power of the printed page. (3B)

Seeing a phonograph

in a period piece movie is another example of how time traveling

can be triggered. Watching a movie set in 1903 and seeing a gramophone

with its open horn sitting on the parlor room table is a time

period encounter and that experience can become part of your memory.

You associate a gramophone with a time and place. Hearing music

on that gramophone further enhances that memory and as Harvith

summarized in quoting musicologist James Hepokoski,

"Music of the past tells us what it felt like to live during

the period when it was created." (3C)